By Van T. Cotter, Ph.D., Herbarium Associate (and fungi expert!)

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU)

A discovery

While visiting Mason Farm Biological Reserve on March 22, I came upon a grape vine covered with orange slime. A portion of the slime was covered with a frothy white material which smelled wonderfully of yeast. Intrigued by the odor, I wondered if I could capture the microorganisms in the froth and use them to make sourdough bread.

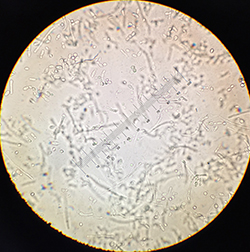

Conventional bread uses just one microorganism: bread yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Sourdough bread, on the other hand, uses a starter with a community of microbes, both fungal (yeasts) and bacterial. I took a small amount of the froth home to examine microscopically. And no disappointment, the froth was comprised of a microbial community of at least 3 members, one of which was a single-celled budding yeast. The other two were another yeast with short filaments (hyphae) and a rod-shaped bacterium.

Could this wild microbial community be put to work as sourdough starter?

I used the white froth to inoculate a mixture of bread flour and bottled water (Ratio: 2:1) and fed the starter daily with 1 cup flour and 0.5 cup water.

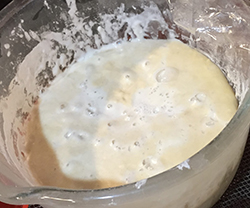

Success! The starter developed nicely as illustrated by the bubbling and it passed the float test. The float test is a quality control test; if the starter floats then the starter is good (active). It means the microbial community is producing enough carbon dioxide to make the starter lighter than water.

But would the Mason Farm-derived starter make a good bread?

Loaf Trials

The dough for the first two loaves looked like cow pies not holding any shape. Loaf 1 was heavy but did have a fine sourdough tangy flavor and nice chewy texture. I added some commercial yeast to Loaf 2, which did make it lighter in texture.

Two possible reasons for the weakness of the rise in the first two loaves are that the starter was young and not yet up to speed and I incubated the dough at a high temperature – greater than 90 F. I decided to use 85 F as the incubation temperature in my next trials.

Loaves 3 and 4 turned out fine with no help from commercial yeast, with medium texture and a fine sourdough flavor! The microbial community from Mason Farm came through. Loaves 3 and 4 were even lighter in texture; clearly the nature of the starter was evolving. Usually it takes up to a week to build a new starter, but I rushed things with Loaves 1 and 2 on day 1, and Loaves 3 and 4 on day 5.

Finally, I got to Loaves 5 and 6 on day 7 of the starter. What a difference!

Microbes from many sources end up in sourdough starters – from the flour used, from the air, etc. And the microbial community of yeasts and bacteria in a starter may shift over time. Truth be told, there is no guarantee that the Mason Farm microbes are the main actors or will remain the main actors in my Mason Farm Sourdough Starter, though of course I would like to think so. If I were to do it again, I would identify the microbes (the microbiome) in the starting material found in nature using microscopy and molecular methods, then do the same once the sourdough starter is established to see which of the starting microbes ended up in the starter microbiome.

The Bottom Line

Mason Farm-derived sourdough starter makes fine bread. And I would be happy to share Mason Farm Sourdough Starter with anyone who would like to give it a whirl when stay-at-home orders are lifted.

A variety of yeasts (fungi) and bacteria are found in sourdough starters as investigated by Rob Dunn’s Lab at North Carolina State University. See: http://robdunnlab.com/projects/sourdough/map/

Carol Ann McCormick, Herbarium Curator, adds this book recommendation: Sourdough by Robin Sloan. The novel is available as an e-book or audio recording via many public libraries. Happy baking and reading!

Recipes

Notes

- Flour can be unbleached Bread Flour or All-Purpose Flour. Due to COVID-19, flours especially Bread Flour are in short supply. Of course, one can go in whole or part with whole wheat, rye, etc., flour.

- Water can be tap or bottled. I boil the tap water to reduce the chlorine.

- Many items such as nuts, say pecans, or dried fruit can be added.

- I’m incubating the starter and dough on an 85 F cookie sheet. Often cooler temperatures are used (even a 12-hour period in the refrigerator for the dough) to enhance flavor.

Starter Maintenance – Keep in ceramic or glass bowl.

- Daily add 1 cup flour and 0.5 cup water and mix. Cover with plastic wrap.

- Incubate at 85 F.

Bread – Makes 2 loaves. (Adaptation of Sourdough White Bread Recipe p. 758 in Rombauer, Irma S., Marion R. Becker and Ethan Becker. 1997. Joy of Cooking. Re. Ed.).

- Add 2 cups starter to and mix with 1.5 cups 110 F water in ceramic or glass bowl.

- Turn in 4 cups flour thoroughly mixing.

- Cover with plastic film and incubate 1 hour on 85 F cookie sheet. To maintain temperature, I place starter/dough on a cookie sheet over a Sigg food dehydrator (Figure 4).

- Mix 4 teaspoons salt with 0.5 cup flour.

- Add to and mix with the incubated starter/flour dough by folding. Those who enjoy gooey stickiness with love the folding steps.

- Cover with plastic film and incubate 1 hour on 85 F cookie sheet.

- Fold dough over and over.

- Coat the insides of 2 bread pans with butter.

- Divide the dough into 2 pieces twisting each piece and shaping into a cylinder with rounded ends then place in bread pan.

- Cover bread pans with plastic wrap and then incubate on 85 F cookie sheet overnight. Note: If bread rising quickly, refrigerate for rest of overnight cycle once it reaches desired size.

- The next morning, place large water filled pie plate in bottom of oven and heat oven to 425 F.

- Bake 30 minutes turning bread pan(s) midway.

- Enjoy!

*Mason Farm Biological Reserve is a 367 acre tract managed by the North Carolina Botanical Garden. As this is a site for research, you must fill out a permit form before visiting (https://ncbg.unc.edu/visit/mason-farm-biological-reserve/mfbr-permit/ ) and no dogs are allowed. The Parker Preserve, 127 acres in area, is adjacent to MFBR, no permit is required, and all dogs must be on leash at all times. (For directions and more information, go to https://ncbg.unc.edu/visit/preserves-and-natural-areas/ .) Please exercise responsible social distancing when using these natural areas.

Acknowledgement: Review of this document by Meriel Goodwin is most appreciated.