By Derick B. Poindexter, Postdoctoral Plant Systematics Researcher, UNC Herbarium

Relationships can be a fickle thing. You spend a tremendous amount of time building an understanding of what constitutes a species and memorizing a binomial, and then some taxonomist (probably during the winter months while nothing is in flower) goes and messes with it. That pretty little box that we humans like to construct around species, the one with nice clean edges and a name to match, gets mired. Why, you might ask? Well, as much as we like to organize things into discrete piles, biological reality isn’t so neat. Consequently, our naming conventions must follow science, and they do so dynamically.

Which brings me to a recent name Alan Weakley (director of the UNC Herbarium) and I gave to a new variety of what I thought was a fairly stable friend, bottle-brush grass (Elymus hystrix L.). Whether you like to admit it or not, this species is pretty charismatic for a grass. In fact, it’s likely one of the very few species of Elymus that can be readily identified at a distance by most casual observers. After all, those spikelets that lean way out from the rachis are hard to miss. Whether you are into native gardening or not, it’s difficult not to appreciate this species.

Growing up in the mountains of North Carolina, I spent many a good day exploring outside, and though I didn’t know its name at the time, I was more than familiar with this plant. It wasn’t until recently that I began to pay close attention to it, though. And by close, I mean really cogitating on its morphology (i.e., its physical characters).

From my early experience, I remembered a plant that didn’t seem to produce much in the way of glumes and if so, they were not consistent within an inflorescence. Glumes, by-the-way, are the little leaf-like structures that are often paired at the base of each spikelet. Most manuals said they were small to absent, with the exception to Flora of North America, which allowed for outliers 10(-20) mm long, which I presumed were not encountered often as I had never seen an example in my many years botanizing. And though on rare occasion I would find plants at higher elevations that would have hairs on their spikelets (Elymus hystrix var. bigelovianus (Fernald) Bowden, a variety primarily distributed in northern North America), they were otherwise very much like our old typical Elymus hystrix – non-glumey.

So, when I moved to Chapel Hill in the Fall of 2012, I was immediately surprised by the Elymus hystrix I was seeing. Every plant I encountered in Orange County had glumes on every spikelet, and big ones, ranging from ca. 10-20 mm long. My “something-ain’t-right” alert system went off and my interest was piqued. As I began to look into this in a more systematic fashion, scrolling through herbarium sheets, it became clear that this plant was the dominant form of Elymus hystrix in the Piedmont. But how could this be?

Turns out that I was not the only one who noticed this. Many of our specimens had been annotated by Julian Campbell (an Elymus expert) noting the presence of subequal glumes. In their treatment of the genus for Flora of North America, Barkworth et al. (2007) acknowledged that most of this long-glume material occurred in the Carolina Piedmont region, presuming it was of local hybrid origin, likely introgression with E. glabriflorus (Vasey) Scribner & C.R. Ball. While this may very well be the case, the dominance of this form in the Triangle and Piedmont of neighboring states suggests that it is genetically fixed, and if we are to recognize other varieties (like var. bigelovianus) based on biogeography and morphology, it only makes sense to recognize this plant as a variety as well. So, we opted for a name that was most fitting for this plant’s Piedmont-centered distribution, Elymus hystrix var. piedmontanus D.B. Poind. & Weakley.

If you would like to see this plant in all its glory, don’t worry as it is easy enough to find in the Triangle. Take a stroll around Coker Arboretum or Forest Theatre in June and you can’t miss it.

Perhaps a new name will bring more attention to this variety, as much additional research is needed to understand the age-old question of how it came to be. In the meantime, it’s nice to better understand the nuances of an old friend…at least until winter rolls around and taxonomists have more time on their hands.

References

Barkworth, M.E., J.J.N. Campbell, & B. Salomon. 2007. Elymus. In: Barkworth et al. (eds.), Flora of North America vol. 24.

Weakley, A.S., D.B. Poindexter, R.J. LeBlond, B.A. Sorrie, E.L. Bridges, S.L. Orzell, A.R. Franck, M. Schori, B.R. Keener, A.R. Diamond, Jr., A.J. Floden, and R.D. Noyes. 2018. New combinations, rank changes, and nomenclatural and taxonomic comments in the vascular flora of the southeastern United States. III. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 12(1):27-67.

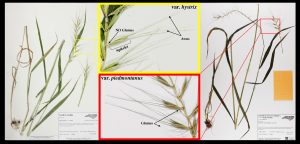

Figure 1. Elymus hystrix of the North Carolina Piedmont. A) Var. piedmontanus (white arrow pointing to base of a shed spikelet with paired long wiry glumes. B) Var. hystrix (white arrow depicting base of intact spikelet without glumes).

Figure 2. Elymus hystrix of the North Carolina Piedmont. A) Var. piedmontanus (white arrow pointing to base of a shed spikelet with paired long wiry glumes. B) Var. hystrix (white arrow depicting base of intact spikelet without glumes).

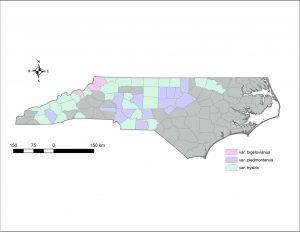

Figure 3. General county-level distribution of the three varieties of Elymus hystrix in NC. The typic var. hystrix also occurs at lower elevations within the montane counties containing var. bigelovianus, as well as those counties with var. piedmontanus in the foothills.

Top photo by Bruce Sorrie