By Carol Ann McCormick, Curator, and Dr. Van Cotter, Herbarium Associate, UNC-Chapel Hill Herbarium

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) curates hundreds of thousands of botanical specimens – fungi, mosses, algae, lichens, ferns, wildflowers, shrubs, trees, and even plant fossils. Every once in a while a specimen catches the eye of a curator. Such was the case this week when Herbarium associate Dr. Van Cotter pulled some specimens of Psilocybe to lend to mycologists at the Garrett Herbarium in the Utah Museum of Natural History at the University of Utah. Alexander Bradshaw, a University of Utah graduate student, is doing a phylogenetic study of Psilocybe and to that end requested a loan of twenty specimens.

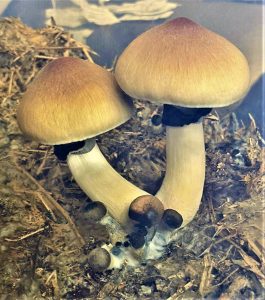

Psilocybe is a genus of gilled mushrooms that are found worldwide. Historically there were about 15 species of Psilocybe in North Carolina, but most have been transferred to other genera, leaving only about 5 species currently in the genus Psilocybe in our region.1 The genus is most famous as the source for psilocybin, which when ingested metabolizes into psilocin, a potent hallucinogen.2

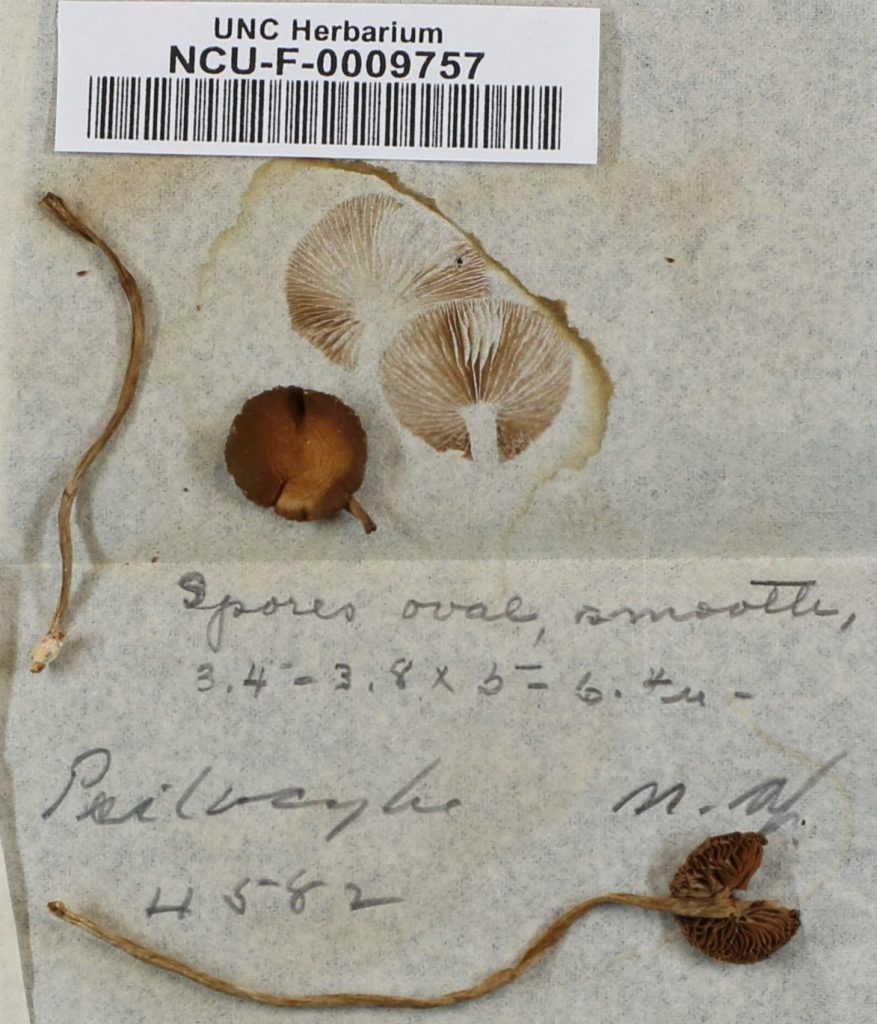

Prior to shipping the specimens to Utah, Dr. Cotter photographed them for inclusion in our online catalog, mycoportal.org. One specimen (NCU-F-0009757) stood out for its strikingly beautiful spore print.

Mushroom spore prints serve a scientific purpose as spore print color is a central character in identifying mushrooms. They are also beautiful works of art with delicate patterns which are the mirror images of the gill or pore pattern of the mushroom. Spore prints come in a variety of colors from snow white to yellows to pinks to many shades of brown to deepest black, even green.3,4

This specimen will celebrate its 100th birthday on July 28, 2020. Perhaps the collector was pondering the events of that month – the East Africa Protectorate was renamed “Kenya” and became a British Crown Colony, revolutionary general Pancho Villa made an agreement with the Mexican government to retire from hostilities, and Babe Ruth tied his record of 29 home runs in a season during July, 1920.

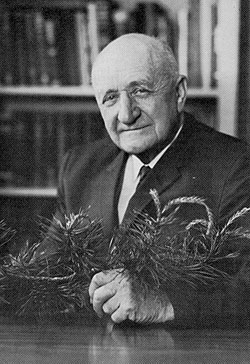

The diminutive Psilocybe specimen was collected by Henry Roland Totten (1892-1974) who earned his A. B. and M.A. from UNC-Chapel Hill in 1913 and 1914, respectively. It would have been while he was a doctoral student with renowned mycologist Dr. William Chambers Coker that he collected this particular Psilocybe specimen. Upon completion of his Ph.D. in 1923, Totten joined the Botany Department at Carolina and taught general botany, dendrology, pharmacognosy, and plant taxonomy. Totten served as a Director of the Coker Arboretum and was instrumental in founding the North Carolina Botanical Garden.

This Psilocybe fungus was collected “by Bowlin’s Creek [sic; Bolin Creek] at Fern Walk” – a favorite botanizing locality of Totten’s. “Topography Chapel Hill and Vicinity” by Thomas F. Hickerson and W. F Morrison dated 1918 shows “Fern Bank Walk” to be in the vicinity Umstead Park in Chapel Hill, near the confluence of Tanbark Branch and Bolin Creek.5

The label shows many people studied the specimen – Totten himself filled in the collection date, while his doctoral advisor, Dr. Coker, filled in the scientific name, location and copious notes on the physical characteristics of the fungus. Ms. Alma Holland Beers, the first woman hired by the Botany Department as a Research Assistant, examined the fungal spores and noted their shape and dimensions.

It is interesting that Dr. Coker only identified the fungus to genus, not to species. In fact he notes “n. sp.” on the label indicating that he considered it a “new species”. We look forward to Alexander Bradshaw’s analysis of the DNA of this Psilocybe. Perhaps this specimen’s genetic sequence will match a known fungus and we can finally fill in the species name. Or perhaps its genetic sequence will not match any other and for its 100th birthday it will get a name of its own.

- For an example of a generic shift, Psilocybe cokeri Murrill, named in 1923 in honor of UNC-CH mycologist William Chambers Coker (1872-1953), was transferred to a different genus in 1972. It is now Psathyrella cokeri (Murrill) A. H. Sm. The holotype, curated by New York Botanical Garden Herbarium (NY), was collected by William Battle Cobb (1891-1933) on 24 October, 1913 “In low leafy place near branch below Meeting of Waters [in Chapel Hill].”

- Wikipedia contributors. “Psilocybe.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 16 May. 2020. Web. 17 Jun. 2020.

- Chlorophyllum molybdites, a beautiful stately fungus that forms large fairy rings in lawns, is the only local mushroom that produces green spore prints. Green spore print = beware! as Chlorophyllum causes more mushroom poisonings in the United States than any other mushroom. Not fatal, but may be severe with hospitalization required.

- HOW TO MAKE A SPORE PRINT: The simplest way is to cut off the stem of the mushroom then place the cap onto paper. You may want to have several mushroom caps and several different colors of paper, since it you want the color of the spores to contrast with the color of the paper. Cover the mushroom with a bowl and wait. Depending on the species, stage of development, temperature, etc., a spore print may form within a couple hours or require overnight. If you are unlucky and your mushroom is, unbeknownst to you, full of ravenous maggots you will have mush instead of a spore print. It happens. But if all goes well you will have a beautiful spore print!

- Hickerson, Thomas F. and W. F. Morrison. 1918. Topography, Chapel Hill and vicinity, Orange County, North Carolina. T. F. Hickerson and W. F. Morrison, Chapel Hill, N.C. (In the North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/ncmaps/id/1083/rec/27 accessed on 18 June 2020.