By Carol Ann McCormick, Curator, UNC-Chapel Hill Herbarium

One of the few good aspects of the restrictions on school, social, and business activities this past spring has been that people have flocked to the outdoors. Many who had never before visited Seven Mile Creek Preserve (in Hillsborough), Duke Forest (in Alamance, Orange and Durham Counties), and the NCBG Parker Preserve were exploring these wonderful places.

I chose to leave these places to newcomers, and took the opportunity to widen my horizons for new places to see wildflowers. One of the side benefits of cataloging the many thousands of plant specimens in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) is that I learn about places that have interesting plants. I can then make those places destinations. On a clear Saturday in early May my husband and I decided to explore Rocky Face Mountain. An added draw was that we had never even set foot in Alexander County in the nearly 3 decades we’ve lived in North Carolina.

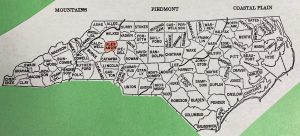

Rocky Face Mountain is an outlier of the Brushy Mountains which start near the city of Lenoir in Caldwell County and run northeast through Alexander, Wilkes, and Iredell Counties before ending near the town of Elkin in Yadkin County. The “Brushies” themselves are an isolated spur of the larger Blue Ridge Mountains to the west. Pores Knob, the highest peak in the Brushies at 2,680 feet (817 m) in Wilkes County, was a favorite botanizing spot of Laurie Stewart Radford, Curator of the Herbarium in Chapel Hill from 1937 to 1942. Laurie grew up on Sunland Orchard in Wilkes County and earned her Masters degree in botany at UNC-Chapel Hill.1,2,3 Orchards have long been important to the economy of the area. The Brushy Mountain Apple Festival is still scheduled to occur in North Wilkesboro on October 3, 2020, but the annual Bushy Mountain Peach & Heritage Festival in July was cancelled for this year due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Mining and quarrying are also important to the economy in the Brushies. Emeralds and hiddenite (a green variety of spodumene) are found in the Hiddenite Gem Mines in Alexander County.4,5 Alas, there are no emeralds at Rocky Face Mountain — it was a rock quarry. According to David Odom, Town Manager of Taylorsville, “Prisoners from the jail out on Highway 16 south of town were brought out to the quarry at Rocky Face. This would have been in the 1920’s until maybe the 1940’s. They would bust up the rocks then load the gravel and rocks into railroad cars. You can still see the remnants of that railroad spur in some places as you head out to Rocky Face.”6

While the plant life at Rocky Face Mountain may have been well-known to the local inhabitants, botanists associated with university herbaria began to document the flora in the 1930’s: Otto Veerhoff’s specimens are in the NC State Herbarium, while those collected by William Chambers Coker, H. R. Totten, and Thomas Grant Harbison are in the Herbarium at UNC-Chapel Hill. During the 1940’s Catherine Keever of Duke University collected plants throughout the Brushy Mountains, including Rocky Face. By the 1950’s, botanists from Davidson College (Tom Daggy), UNC-Charlotte (Herbert Hechenbleikner and James Matthews), and UNC-Chapel Hill (Al Radford) were studying the flora of Rocky Face. During the 1970’s the vegetation of the Mountain’s rock outcrops was studied by botanists from Duke University (Robert Wyatt) and Western Carolina University (James Horton).

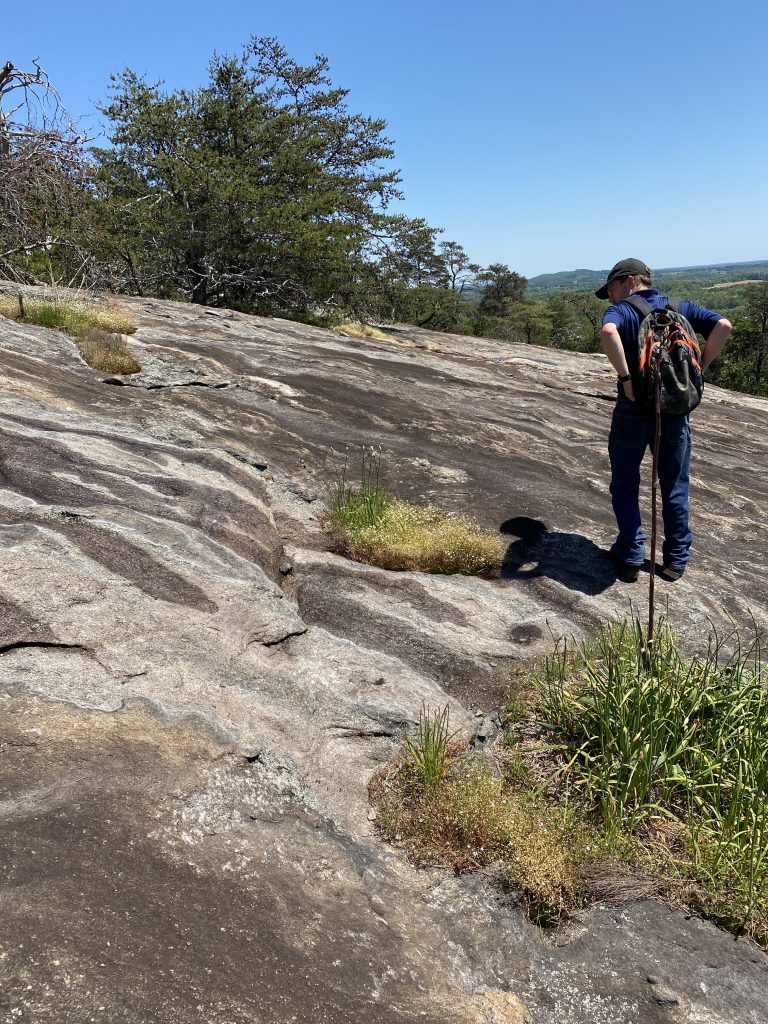

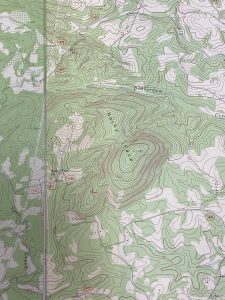

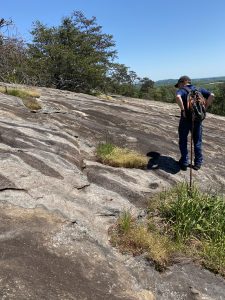

Rocky Face Mountain was surveyed by biologists with the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program in 2002. “Rocky Face Mountain with its extensive exposures of granitic gneiss and areas of shallow soil contains examples of rare natural community types, including Low Elevation Granitic Dome and Montane Red Cedar – Hardwood Woodland, along with good examples of the uncommon Piedmont Monadnock Forest type. [It] contains a number of rare species associated with rock outcrops and forest and woodlands. These include Keever’s bristle moss [Orthotrichum keeverae] which is considered endangered by the state [with] most of its world population is in the Brushy Mountains. Also included are striped garlic [Allium keeverae], shinyleaf meadow-sweet [Spiraea corymbosa] , cofaqui giant skipper [Megathymus cofaqui] and [eastern] giant swallowtail [Heraclides cresphontes]. Rocky Face Mountain is an excellent example of a granitic dome or bornhardt, and of the exfoliation process in the massive granitic rock that creates the rock faces.”7 Thanks to funding from the NC Parks & Recreation Trust Fund, the Carolina Land & Lakes Resource Conservation & Development District, and the Felbourn Foundation, this special place was preserved for the enjoyment of all. Rocky Face Mountain Recreational Area opened in 2012.8 The former quarry site now hosts the park’s picnic area, restrooms and rock climbing/rappelling facilities – all currently closed due to Covid-19. However the 5 miles of trails in the 381-acre park are open, and when my husband and I visited in early May we were among the few venturing on the trails. Midway through our trek we encountered Park employee Bob Russo, who enlightened us as to the diverse reptiles found on the Mountain.

The Buzzard Loop Trail started our botanizing out with a bang – Appalachian Sandwort (Mononeuria glabra), Michaux’s Saxifrage (Micranthes petiolaris) and Elf Orpine (Diamorpha smallii) were in full bloom on the gently sloping granite rocks. I felt as though we were following in the footsteps of our botanical foremothers and forefathers, as the Herbarium curates specimens from these very species collected from Rocky Face in 1937. While I had seen herbarium specimens of the very rare Keever’s Onion, it was a highlight of our May hike to see the plant in bloom in its natural habitat. Allium keeverae occurs only in the Brushy Mountains of Alexander and Wilkes Counties. “This is the Piedmont’s most beautiful species of Allium, when in bloom… If you are able to visit one of these granitic domes in the Brushies, a visit in the latter part of May can yield a stunning floral display of dozens of these rare plants in bloom.”9

Once I returned home I was even more determined to mine the Herbarium for more information on the botany of Rocky Face Mountain. As the Herbarium in Chapel Hill has only 821 specimens from Alexander County as a whole, I made it a Pandemic Priority to get all those records complete in our database. After a few weeks of typing, I now know that of those 821 specimens, 215 were collected at (or near) Rocky Face. While I was familiar with most of the academic botanists who visited Rocky Face, I was less familiar with the dedicated amateur local botanists who contributed to our knowledge of its flora. “Rev. Raynal” and “Dr. Hoffmann” are mentioned on many specimen labels from plants collected in the 1930’s, and I was curious about these two Citizen Scientists.

Charles Edward Raynal was born on 17 March 1877, son of Pierre Napolean Raynal of Ste. Marie-aux-Mines, Alsace, France and Rebecca Ann Girardeau of Liberty County, Georgia. He earned a Doctor of Divinity degree from Davidson College in 1914. After serving as pastor in Birmingham, AL and Charlotte, NC, he served as pastor at First Presbyterian Church in Statesville, NC from 1909 to 1944. “A botanist by avocation, Charles E. Raynal acquired a substantial botanical library including many first edition copies of works by Carolina botanists…He was a committed conservationist, a fact reflected both in his collections of scientific articles, pamphlets, on books and in his own writings.”10 Among the woody species that caught Raynal’s attention was Magnolia macrophylla, and it is a specimen of that tree collected from woods near Statesville, Iredell County, NC in September, 1932 which is the first specimen he deposited in the Herbarium in Chapel Hill. Raynal sent live specimens to Coker and to Coker’s research assistant, Alma Holland Beers. The tree planted in Beer’s yard in the Gimghoul neighborhood in the 1930’s still grows there today, and many mature trees can be found naturalized in nearby Battle Park.10

Herbarium specimens reveal that Rev. Raynal botanized with fellow Statesville resident Dr. Solomon Wallace Hoffmann, an osteopathic physician from a family with deep botanical roots. To explore those roots, I delved into the history of Statesville, Iredell County, North Carolina.

The growth of Statesville was spurred by the arrival in 1858 of a station for the Western North Carolina Railroad which ran from Salisbury (Rowan County) to Morganton (Burke County).11, 12 David and Isaac Wallach (which they anglicized to “Wallace”), Jewish immigrants from Germany, opened a general store in Statesville ca. 1868. “In addition to general merchandise, the brothers also bought and sold medicinal herbs, which soon grew into a major operation. In 1871, they hired Mordecai Hyams [a Jewish man from Charleston, S.C.] who was an expert in roots, barks, and herbs, to be their botanical manager and built a two-story warehouse to store the product. Hyams established ties with rural farmers and merchants around the state, who would ship the herbs they had found to Statesville in return for other goods. Hyams scoured the countryside looking for new herbs to sell. After five years, Hyams had expanded their herbal products from 30 to 700. Hyams gained national attention and acclaim for his work. By 1876, their herb operation was doing over $50,000 in business, as herb gathering kept many rural North Carolinians afloat during the economic panic of the 1870s. By the late 1880s, their sales volume had surpassed $100,000 a year. The Wallace brothers eventually closed their retail store, focusing their efforts on their booming wholesale herb business, which had customers around the country and in Europe… The Wallace brothers had a significant impact on Statesville and its Jewish community. Isaac and David used the proceeds from their highly successful herb business to invest in other ventures, including the purchase and renovation of the Cooper Hotel, a local cotton mill, and creation of a suburban housing development south of the city … In 1879, Jacob Hoffman moved to town from Bamberg, South Carolina; he initially worked for the Wallace brothers before opening his own dry goods store.”13

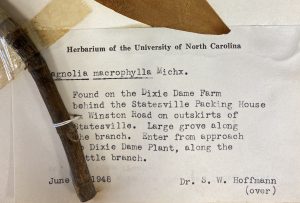

Jacob Hoffmann married Fannie Wallace, daughter of David Wallace, and their son Solomon Wallace Hoffmann was born in 1885.14 S. Wallace Hoffmann became an osteopathic physician and lived his whole life in Statesville.15 No doubt with the family in the “botanicals business” and his medical education, which likely included pharmacognosy (the study of drugs from plants and other natural sources), Wallace Hoffmann had a good grasp of botany. The earliest specimen NCU curates collected by Dr. Hoffmann is the carnivorous plant, Sarracenia flava, collected “near Rocky Face Mountain” on May 21, 1937. It is interesting that the last specimen we have collected by Dr. Hoffmann, dated 4 June, 1948, is Magnolia macrophylla, the plant which so interested his friend, Rev. Raynal.

Dr. Hoffmann and Rev. Raynal were joined on a botanical trip to Rocky Face Mountain on May 21, 1938 by Chapel Hill botanist Dr. Henry Roland Totten (1892-1974), Totten’s spouse, Adelaide Williams “Addie” Totten (1889-1974), and Sarah Noe. (I have no information about Ms. Noe — if you do I’d love to hear about her!) It was a busy botanical day, and they collected 20 specimens, among them Pinus pungens, Allium keeverae, Spiraea corymbosa, Rhus aromatica, Viburnum nudum, Callicarpa americana, Rhododendron viscosum, and Sarracenia purpurea. I trust that Wallace, Charles, Henry, Addie and Sarah enjoyed a lovely lunch on the open rocks, listening to ravens and pointing out landmarks in the surrounding countryside, just as Mark and I did nearly 82 years later.

In May, 2021, I plan on leading a NCBG field trip to Rocky Face Mountain – look for details in spring newsletters and join me!

SOURCES:

- Wikipedia contributors, ‘Pores Knob’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 December 2018, 11:24 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pores_Knob&oldid=875048201> [accessed 29 July 2020]

- Wikipedia contributors, ‘Brushy Mountains (North Carolina)’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 12 April 2020, 00:02 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Brushy_Mountains_(North_Carolina)&oldid=950415642> [accessed 29 July 2020]

- Burk, William R. 2005. Laurie Marguerite Stewart Radford: A Tribute. Chinquapin 13(1): 4a.

- Wikipedia contributors, ‘Hiddenite Gem Mines’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 6 September 2019, 14:28 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hiddenite_Gem_Mines&oldid=914308226> [accessed 29 July 2020]

- Wikipedia contributors, ‘Hiddenite’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 9 September 2018, 16:55 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hiddenite&oldid=858792120> [accessed 29 July 2020]

- Pers. comm. David Odom, Taylorsville Town Manager, phone conversation with McCormick, 22 July 2020.

- ‘Plant / Animal Life’, Rocky Face Mountain Recreational Area, 2020, <https://rockyfacepark.com/plant-life/ > [accessed 29 July 2020]

- ‘History of Rocky Face’, Rocky Face Mountain Recreational Area, 2020, <https://rockyfacepark.com/history-of-rocky-face/ > [accessed 29 July 2020]

- ‘Account for Keever’s Onion – Allium keeverae D.B. Poind, Weakley, & P.J. Williams’ LeGrand, H., B. Sorrie, and T. Howard. 2020. Vascular plants of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https://auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/flora/index.php [accessed 29 July 2020]

- ‘Charles Edward Raynal’ McCormick, Carol Ann, Lisa Giencke and Dudley J. Raynal. 2020. Collectors of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium. <https://ncbg.unc.edu/2020/07/23/charles-edward-raynal/ > [accessed 29 July 2020]

- ‘Statesville History’ <https://www.co.iredell.nc.us/629/Statesville> [accessed on 25 July 2020]

- Wikipedia contributors, ‘Western North Carolina Railroad’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 3 March 2019, 19:44 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Western_North_Carolina_Railroad&oldid=886013521> [accessed 25 July 2020]

- ‘Statesville, North Carolina’ Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities. <https://www.isjl.org/north-carolina-statesville-encyclopedia.html> [accessed on 25 July 2020]

- ‘Death Certificate, Fannie Wallace Hoffmann’ North Carolina State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics. North Carolina Death Certificates. Microfilm S.123. Rolls 19-242, 280, 313-682, 1040-1297. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, North Carolina. Ancestry.com. North Carolina, Death Certificates, 1909-1976 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2007.

- ‘Dr. Hoffmann Stricken’ Statesville Record & Landmark, Statesville, NC. Saturday, 14 August, 1971.