(1910 – 2004)

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) curates over 1200 vascular plant specimens collected (or co-collected) by Laurie M. Stewart Radford. NCU also curates about 25 fungal specimens collected by Stewart Radford from the area around the Highlands Biological Station in Macon County, North Carolina. She usually used “L. M. Stewart” or “L. S. Radford” on specimen labels.

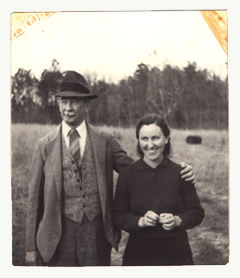

Laurie Marguerite Stewart was born 29 August 1910 in Roanoke, Virginia to Samuel Converse Stewart and Irene Falconer Stewart. She spent most of her childhood in the Brushy Mountains of Wilkes County, North Carolina. She graduated from Appalachian State Teachers College in Boone, N.C., then earned a master’s degree in botany from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1937. The title of her Masters Thesis was “Studies in the life history of Nitella hyalina Agardh.” and her thesis advisor was Dr. William Chambers Coker.2

Coker is acknowledged as founding the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium ca. 1908 when Davie Hall was built with space devoted to herbarium specimens. “There was no sense of urgency nor concentrated effort to build up a sizable collections as soon as possible. Specimens were added from time to time as collected, now that there was a safe place in which to keep them. This is understandable, considering the scope of Dr. Coker’s [administrative and teaching] responsibilities,” wrote Stewart Radford in 2000. It was not until 1932, upon the death of UNC-Chapel Hill alumnus William Willard Ashe, that the Herbarium’s collection of vascular plants grew exponentially. “Ashe’s plants were all over the place, under tables, on the tops of cabinets, in corners — not just a hundred or so specimens, but 20,000 or more… Someone was needed to give undivided attention to deciphering Ashe’s “peculiar signs and symbols,” as Dr. Coker described the shorthand that Ashe often used on his specimens in the field. [Ashe’s herbarium] was for the most part unmounted… so much work was needed to get it into shape to be used.” (2) Dr. Thomas Grant Harbison, a personal friend of both Ashe and Coker, was hired to be the Herbarium Curator, and he began in that capacity in the autumn of 1934. At Dr. Coker’s direction, Stewart began working in the Herbarium in the fall of 1935, assisting Harbison and directing the work of undergraduate students. Dr. Harbison was in poor health when he started at Carolina, and he died in January, 1936. “The confusion would be compounded by the arrival of some additional 12,000 specimens from the Harbison Herbarium, recently purchased from his widow… In April [1936] I learned from Alma Holland, Dr. Coker’s secretary, that Dr. Coker was planning to offer me the job of full-time curator of the herbarium as soon as I received my master’s degree.”1

Ms. Stewart served as the Curator of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium from 1937 until 1942. “The first day back on the [herbarium curator] job in September [1939], I found my newest assistant [Albert E. Radford] already there ahead of me, checking out the herbarium. Before I could tell him I was going to put him to work on the backlog of unidentified specimens, he let me know that he had no interest in gluing plants to paper — that would be a waste of his time. All he wanted to do was to identify plants. A bit miffed, to say the least, at being told how to run the herbarium, I nevertheless held my tongue. I needed an “identifier” not another gluer”; some day I would set him straight. Come to think of it, many years later he has yet to mount his first plant…”1

In 1941 she married Albert E. Radford and together they had three children: David, John, and Linda.2

In late June of 1942 Stewart Radford took a leave of absence from the herbarium. “I took our four month old son David and went back to Wilkes County to stay with my parents. They needed me — and I needed them. There was no one to help them with farm or orchard. Young men were leaving schools, factories, offices, and farms by the thousands to join the Armed Forces… It was hard to leave the herbarium. I had become very attached to it and its needs. I had accepted the challenge to bring some order out of its great disorder, mainly the result of the sudden accumulation of some 35,000 specimens from the Ashe and Harbison herbaria, crowded into a space too small and in need of so much attention. Those had been such happy years, full of learning and personal growth, new experiences, good friendships, and most of all a gratifying sense of accomplishment. I recalled some of our accomplishments: most of the Ashe and Harbison collections had been processed and filed; all those bundles, gathering dust for years, had been taken down from the tops of the cases and cared for; a good start had been made toward putting the cases in order; a drier that worked had been built; herbarium cases had been increased to 47 and now occupied the entire second floor back wing of Davie Hall; an efficient workroom had been set up at the back and a neat office in the front. Botanists were coming from many places to study in our herbarium… In the short time that Albert [Radford] had worked there, he and I collected around 11,000 specimens. The herbarium had grown from 74,000 specimens in 1935 to close to 10,000 by the time I left in 1942… The work of the herbarium would slow down and most of our projects would be put on hold. Our nation was at war, and there were more important things to attend to now. The herbarium would have to wait. It was in good shape.”1

Ms. Radford wrote seven articles for the 1984-1986 issues of the Friends of the Herbarium newsletter. Each article focused on a specific era in the development of the herbarium. In 1998, she updated the articles and compiled them into a single 50-page history of the NCU Herbarium, The History of the University of North Carolina Herbarium at Chapel Hill, NC 1908-1998.

“With the death of Laurie Stewart Radford, age 94, on November 28, 2004, in Columbia, Missouri, we have lost a friend and botanist whose intelligence and care touched so many, ” wrote Bill Burk, a colleague at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.2

SOURCES:

1. Radford, Laurie Stewart and Albert E. Radford. 2000. The Herbarium of the University of North Carolina, 1908-2000. History and Persepctive. The Herbarium (NCU), University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. 104 pp.

2. Burk, William R. 2005. Laurie Marguerite Stewart Radford: A Tribute. Chinquapin 13(1): 4a.

PUBLICATIONS:

Stewart, Laurie M. 1937. Studies in the life history of Nitella hyaline Agardh. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 53: 173-190.

Radford, L. S. 1974. Botanical Names. Chapter 4, pp. 57 to 82, in Vascular Plant Systematics, by A. E. Radford, W. C. Dickison, J. R. Massey, C. R. Bell. Harper and Row, New York.

Radford, Laurie Stewart. 1991. Our Mountaintop Experience… Seems Like Only Yesterday… [Privately published by Laurie Stewart Radford, Chapel Hill]. 119 pp.

Radford, Laurie Stewart and Albert E. Radford. 2000. The Herbarium of the University of North Carolina, 1908-2000. History and Persepctive. The Herbarium (NCU), University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. 104 pp.