By Carol Ann McCormick, Curator, UNC-Chapel Hill Herbarium

On a recent Sunday in June, my husband and I decided to take a walk at the Confluence Natural Area. We arrived at the Confluence at about 9 a.m., before the heat and humidity soared, and walked the shady trails until just past noon. Located in central Orange County between Hillsborough and Cedar Grove, the Confluence is owned and managed by the Eno River Association, and the 200-acre preserve is where the east and west forks of the Eno River merge to form the the Eno River. It is a Nationally Significant Natural Heritage area, and home to populations of several rare plant species.

A plant I particularly enjoy seeing at the Confluence is Circaea canadensis, “Enchanter’s-nightshade.” We’ve usually found Circaea in several spots along the 1.75 mile-long Two Forks Trail, but on this visit we saw it everywhere — sometimes it was the dominant plant on the forest floor. As with many wildflowers, it is most easily spotted when it is in bloom, and we must have chosen its peak bloom day by chance. It is not a rare plant in the Piedmont of North Carolina, but all the same, it is not a wildflower that I see terribly often. I collected a specimen in 2018 from the Confluence and it joined the handful of Circaea specimens collected in Orange County over the past eight decades curated by the Duke University Herbarium (DUKE) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU):

Circaea intermedia Ehrb. On stream bank at south end of Uni. Lake [University Lake], Chapel Hill. Moist soil, shady place. Botany Class, 19 August 1937. (Annotated to Circaea lutetiana L. ssp. canadensis (L.) Asch. & Mag. by David E. Boufford in 1978) NCU Accession # 60464

Circaea latifolia Hill Deep woods along Creek below Mason Farm, Orange County. William Chambers Coker & Budd Elmon Smith, 1 July, 1941. (Annotated to Circaea lutetiana L. ssp. canadensis (L.) Asch. & Mag. by David E. Boufford in 1978) NCU Accession #22456

Circaea quadrisculcata (Maxim.) Fran. & Sav. Moist, fertile floodplain under well-developed bottomland hardwoods.

Orange County. Duke Forest Natural Area, 7 mi WNW Duke Univ. B. L. Welch #0402 , 25 July 1960. (Annotated to Circaea lutetiana L. ssp. canadensis (L.) Asch. & Mag. by David E. Boufford in 1978) DUKE Accession #146384

Circaea lutetiana ssp. canadensis (L.) Asch. & Magnus Gate 32 of the Hillsborough Division of the Duke Forest just W of Hillsborough on Route 70 and W of Eno River. Erect herb. Petals white. Rare. Robert L. Wilbur #47929. DUKE Accession # 330846

Circaea lutetiana ssp. canadensis (L.) Asch. & Magnus Hunt Arboretum Grid 23. N side of Morgan Creek. Aspect: F [flat]. alluvial soil NW of sewer road, pine-hardwood bottomland. Julia O. Larke #1366. NCU Accession # 558185.

You will note that there have been many scientific names ascribed to this modest wildflower — the name in vogue now is Circaea canadensis. “The systematics of this taxon is controversial, and the best treatment is still unclear… The complicated synonymy is perhaps an example of a too-zealous attempt to have nomenclature reflect subtleties of relationship and evolutionary divergence, our understanding of which is unclear and changeable,” says Dr. Alan Weakley in his Flora of the Southeastern United States.1

Botanists Harry LeGrand and Bruce Sorrie list two species as growing in North Carolina: Circaea canadensis and Circaea alpina.2

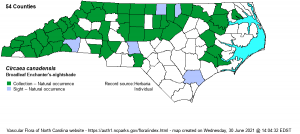

LeGrand and Sorrie call Circaea canadensis “Broadleaf Enchanter’s-nightshade” and describe it as “a very widespread species of the Northeast, found over much of eastern Canada, south to central North Carolina, and the central parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and into Louisiana. This is a species of rich hardwood forests, both in bottomlands and on lower slopes, such as in basic mesic forests and rich cove forests; also it can be found into mesic mixed hardwood forests. Frequent to common across the mountains and most of the Piedmont, except rare in the far southeastern portions. Rare to uncommon in the northern and central Coastal Plain. Seemingly absent in the far eastern and the southwestern parts of the Coastal Plain (including the Sandhills).”2 In the summer of 2020 my husband and I “filled in a hole in the map” by collecting Broadleaf Enchanter’s-nightshade along the banks of Cane Creek in Alamance County. That plant is still in my plant press awaiting a label and accession into NCU — and then inclusion in the map of the NC-Biodiversity website.

You will have to travel to the mountains and hike to elevations well over 4,000 feet to enjoy “Small Enchanter’s-nightshade,” Circaea alpina. According to LeGrand and Sorrie, “This is a widespread North American species, from coast to coast, ranging in the east south to Pennsylvania and northern Illinois, and then south through the Appalachians to southwestern North Carolina and adjacent Tennessee…This is a species of cool and somewhat damp places,

most frequent in spruce-fir forests, or hardwoods mixed with spruce. It can also occur in seepages in forests and near waterfalls and other damp places such as cliff faces with seepage…. [It is] perhaps absent from Cherokee County owing to insufficiently high elevations.”2

A question I have always had about Circaea is how such a small (downright diminutive in the case of C. alpina) plant got such an awesome common name. Circe, for whom the plant is named, is “an enchantress and a minor goddess in Greek mythology… renowned for her vast knowledge of potions and herbs. Through the use of these and a magic wand or staff, she would transform her enemies, or those who offended her, into animals. The best known of her legends is told in Homer’s Odyssey when Odysseus visits her island of Aeaea on the way back from the Trojan War and she changes most of his crew into swine… Her ability to change others into

animals is further highlighted by the story of Picus, whom she turns into a woodpecker for resisting her advances. [Linnaeus named a genus of woodpeckers Picus in 1758.4] Another story tells of her falling in love with the sea-god Glaucus, who prefers the nymph Scylla to her. In revenge, Circe poisoned the water where her rival bathed and turned her into a dreadful monster.”3

I suspect it is not by chance that a main character in Game of Thrones is named Cersei, pronounced much the same as Circe and Circaea.

I can recommend for your summer reading a different take on the story of Circe. Instead of a predatory, sexually promiscuous witch who capriciously tortures men, novelist Madeline Miller gives the goddess a backstory and describes how Circe uses her talents and power in a world ruled by men. In her review of the novel Annalisa Quinn writes, “[Miller] paints another picture: of a fierce goddess who, yes, turns men into pigs, but only because they deserve it… My favorite of Miller’s small recalibrations is less lofty: It has to do with Circe’s hairdo. In Homer, Circe is identified with her “lovely braids.” The usual scholarly gloss on this is that the braids signal not only beauty, but also exoticism, because Eastern goddesses wore their hair in braids. But in Circe, the braids come about in the first moments of the goddess’s magical awakening, when she begins roaming the island to find ingredients for her spells: “I learned to braid my hair back, so it would not catch on every twig, and how to tie my skirts at the knee to keep the burrs off.” It’s a small detail, but it’s the difference between a person of independence and skill, and some male dream of danger, foreignness, and sex, lounging with parted lips while she watches the horizon for ships… This Circe braids her hair because she has work to do.”5

I invite you to braid your hair back, change your shorts and skirts for long pants to keep the burrs and ticks off, and head to the Eno River — to the Confluence, to Occoneechee Mountain Natural Area, to the Riverwalk in Hillsborough, or to Eno River State Park. If you are observant you may encounter Circaea. I would advise you to be quiet and respectful around this Enchantress.

SOURCES:

1. Weakley, Alan S. 20 October 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium, Chapel Hill, NC.

2. LeGrand, H., B. Sorrie, and T. Howard. 2021. Vascular Plant of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https:/auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/flora/index.php.

3. Wikipedia contributors. “Circe.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 Jun. 2021. Web. 30 Jun. 2021.

4. Wikipedia contributors. “Picus (bird).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 18 Jun. 2021. Web. 1 Jul. 2021.

5. Quinn, Annalisa. 2018. ‘Circe” Gives the Witch of The Oddyssey a New Life. https://www.npr.org/2018/04/11/599831473/circe-gives-the-witch-of-the-odyssey-a-new-life accessed on 30 June 2021.

The Confluence Natural Area is located at 4214 Highland Farm Road, Hillsborough, NC, and is open daily from dawn to dusk. It is is open for low-impact recreational uses, such as hiking, picnicking, and photography.