by Carol Ann McCormick*, John Gaskin, Ph.D.#, and Mark Schwarzlaender, Ph.D. %

In late May 2021, Suzanne Cadwell, all-around naturalist and avid contributor to iNaturalist, got a message from Dr. John Gaskin of the United States Department of Agriculture in Sidney, Montana. “I notice that you are the top observer of Andersonglossum virginianum on iNaturalist. Nice job! Up here in Montana and Idaho we are working on biological control of a weedy invasive from Europe, hounds-tongue (Cynoglossum officinale), which is a close relative of A. virginianum. We are in need of some rootstock of A.v., but obviously it grows no closer to us than Illinois (too far). We have tried to raise it from seed but no luck. We need to grow it and make sure the biocontrol insect does not bother this nice native Andersonglossum in any way. So, I was wondering (if you live close to any of your observations) if we might impose upon you for digging up four plants and sending the root stock to us. I have an account to pay overnight shipping and can give further instructions or details of the research. Thank you for even considering this.”

Ms. Cadwell contacted me. “I received this request via iNat for Andersonglossum virginianum root stock. Where I’ve observed it aren’t locations on which I have permission to collect. I noticed that you’d made a few observations yourself in Alamance and thought that if you couldn’t/wouldn’t collect it yourself, you might have some ideas about how I could help Dr. Gaskin.”

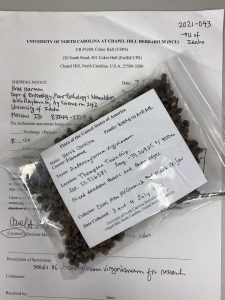

Andersonglossum virginianum (which you may know as Cynoglossum virginianum or “Hound’s tongue” or “Eastern Wild Comfrey”) is a common native wildflower in the mixed hardwood forest around my home in southeastern Alamance County. I took on the task of sending root stock — and later seeds — to Dr. Gaskin and his collaborators, Dr. Bradley Harmon, & Dr. Mark Schwarzlaender at the University of Idaho in Moscow.

I was surprised to learn from Dr. Gaskin’s email that Andersonglossum is difficult to germinate from seed, a situation confirmed by NCBG’s seed program coordinator, Heather Summer. “I’ve had no luck germinating them — scarification followed by stratification might be the answer,” she said.

As soon as the burrs turned brown in late June, I started collecting seeds, with the help of my husband, Mark, and our dog, Luna. The burrs stick to her fur, and she spends ten minutes after every walk pulling them from her fur with her teeth, littering our living room floor with saliva-soaked tufts of fur with embedded burrs.

Andersonglossum virginianum‘s European cousin is Cynoglossum officinale (also called Hound’s tongue), and it has invaded a large part of the northwestern United States. Besides its ability to compete with desirable forage and its toxicity to livestock, it is also infamous for its Velcro-like seeds which cling to cattle, dogs, and shoe laces. Hound’s tongue has few natural enemies in its invaded range, so we work on classical biological control, which is the use of co-evolved natural enemies from an invasive plant’s native range to manage them where they are invasive. Before we can import and release an insect from Europe to attack Hound’s tongue, we perform years of research making sure the insect will not attack anything else, especially native North American plant species. We are especially careful to test species that are close relatives of the weed, so we obtain the closely related native plants, grow them in a quarantine laboratory with the imported biological control candidate insect and perform many tests to confirm that the insect is not attracted to, nor will it eat and reproduce on, the native plants.

Where do we get the native seed for about 100 species that are closely related to Hound’s tongue? We start with GRIN (USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network), a free source of seed for many species, and if that fails we try to buy seed online from nurseries. For many species, there are no options but to collect seed from the field, and this is where herbaria are important. Online herbaria databases with the most recent taxonomic information as well as where and when herbarium specimens were collected in the past, are invaluable. We can download possible locations, gather any necessary permits, and collect a small amount of seed for our research. When a species is threatened, endangered, or at risk, many botanical gardens grow these plants through the Center for Plant Conservation program, and in cases can share seed with us. Often, the botanists from local herbaria have intimate knowledge of the plant locations, population health, and phenology. In this case, we used a combination of iNaturalist observations and herbarium contacts to get the plants and seed needed.

The Andersonglossum virginianum plants from Alamance County, North Carolina are currently growing in a greenhouse at the University of Idaho and will soon be tested against a proposed weevil that evolved with Cynoglossum officinale in Europe. Hopefully the insect will not have any attraction to the native wild comfrey or any other tested natives, but if it does, that will put a halt to the research with that particular biological control agent, and we will have to look for an agent that is more specific. Our goal is to come up with an ecologically sound biological control agent to assist in integrated weed management of invasive European Hound’s tongue.

Throughout this collaboration, there was an interesting canine theme: hound’s tongue, dogs collecting burrs, and two of us have dogs named Luna. “Maybe the key to getting Andersonglossum seeds to germinate are the enzymes in dog saliva — maybe the old hound’s tongue name has something more behind it!” McCormick joked to Gaskin and Schwarzlaender. “I like your thoughts about dog saliva enzymes,” replied Dr. Schwarzlaender. “They are quite different from those of humans and mostly antibacterial. Maybe I could use my Luna to lick peeled Boraginaceae seed prior to putting them in the Petri dish.”

Enjoy finding Andersonglossum virginianum in North Carolina woodlands (with or without canine companionship), refrain from planting the invasive European Cynoglossum officinale in your garden, continue to make iNaturalist observations (you never know who may need them!), and keep reading the NCBG newsletter for updates on Gaskin and Schwarzlaender’s research.

*Curator, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU)

# Research Biologist, Northern Plains Agricultural Research Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Sidney, Montana

% Professor & Associate Director, Center for Research on Invasive Species, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho