(15 June 1872 – 21 June 1947)

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) has, to date, cataloged about 50 specimens collected by Henry Ashby Rankin. He typically signed his herbarium labels “H.A. Rankin”. Most specimens at NCU were collected in Cumberland County, North Carolina. Since he corresponded frequently with John K. Small at the New York Botanical Garden, NY also curates specimens collected by Rankin. In a letter to his son, Henry Jr., dated 6 December 1927, Rankin writes, “[I received a letter] from Dr. Plitt of Maryland University naming about twenty lichens for me. I am sending them at his request and keeping duplicates.” NCU has no lichens collected by Rankin. Other herbaria curating specimens collected by Rankin include Butler University (BUT), Harvard University (GH), Appalachian State University (BOON), and University of South Florida (USF).

Though Rankin was a frequent correspondent with Dr. William Chambers Coker of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and many other notable botanists including John K. Small (New York Botanical Garden), Stephen Hamblin (Harvard University Botanic Garden), C.D. Beadle (Biltmore Herbarium), and Charles C. Deam (Indiana State Forester) , Rankin never attended any university, and it is not known how he came by his love and knowledge of botany.

H.A. Rankin married Douglass Evans in 1896. He passed his love of science on to his children. Henry, Jr. (b. 30 May 1901 – d. 20 November 1999), writing while he is earning his Masters degree in English at UNC-Chapel Hill, thanks his father for a recent letter that included nature notes. “You caught my eye first on the bird note, the pine or blue-winged warbler. I surely would have liked a look at him; the pine warbler I know well enough, and have always longed to see the other. I wish I could see all the birds you come across on the railroad in the spring… It’s [bird watching] a great sport for me, a combination of a number of natural tendencies: love of nature, hunting instinct, beauty and the game of getting up long lists. I can never stop thanking you for starting me off right.” Another son, Samuel Carson, joined his father in running the lumber business. Daughter Douglass “Peggy” Evans Rankin earned a B.A. in biology from Agnes Scott College in Decatur, GA in 1927, did research at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, and earned a Ph.D. in Botany at Johns Hopkins University in 1933. The title of her thesis was “A study of the life history of Polypodium polypodioides with especial reference to spermatogenesis.”

Henry Ashby Rankin is most notable in Southeastern botany for his contributions to the knowledge of two plants, Parnassia caroliniana and Gelsemium rankinii. In 1928, Dr. John K. Small of the New York Botanical Garden named Swamp Jessamine in honor of Henry Rankin, who had discovered the plant. Small’s description was published in Addisonia 13: 37-38.

In 2006 Rankin’s granddaughters, Dorothy and Douglass Rankin, gave his papers to the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. According to the catalogers of this collection:

Henry Ashby Rankin was born in Fayetteville, N.C., and spent most of his life as the owner of a sawmill and plywood business in Cumberland County, N.C. After retirement, he ran a nursery that specialized in native plants of North Carolina. He was an avid amateur botanist and corresponded regularly with members of the botanical community, with whom he exchanged specimens. Two of his botanical achievements were the discovery of a new species of Gelsemium [Gelsemium rankinii Small] and the re-discovery of a plant [Parnassia caroliniana Michaux] first collected and described by the French botanist Andre Michaux and then lost for 125 years. He was a long-time member of the Gray Memorial Botanical Association. He died in 1947. The collection contains correspondence, Rankin’s writings and notes on plants, papers pertaining to Rankin’s plant nursery, printed materials pertaining to flora, clippings of garden columns and other articles, and copies of the Gray Memorial Botanical Association Bulletin, 1933-1944.

Henry A. Rankin was born on 15 June 1872, the youngest of three children born to Capt. Samuel Carson Rankin (1831-1899) and Martha Elizabeth Thom (1837-1872), both of Guilford County, North Carolina. Henry Ashby’s siblings were Walter Lacy Rankin (1868-1904) and Charles Alexander Rankin (1870-1934).

The 1880 census lists 7 year old Henry A. Rankin living on Cool Spring Street in Fayetteville in the household of E.T. & Janie W. McKethan. His relationship to the McKethans is not elucidated. It is interesting that young Henry is not living a few houses away, with A.E. Rankin (28, head of household, merchant), Zula (27, wife), S.C. (48, brother, widower – presumably Henry’s father), Lacy (11, nephew), Charles A. (9, nephew), Nancy A. (32, sister).

The 1910 census shows Henry, 37, living in Fayetteville, Cross Creek Township in Cumberland County, NC. His profession is listed as “lumber manufacturer.” Also in the household are wife Douglas E. [sic] (37), Samuel C. (son, 12), Henry A., Jr. (son, 8), and Douglas E. [sic] (daughter, 7). By the 1930 census, Henry is listed as the Assistant Manager of a veneer plant, son Samuel is a Manager of the veneer plant, Henry, Jr. is teaching English at a college, and both mother and daughter are not employed.

Henry A. Rankin died of arteriosclerosis at 228 Hillside Avenue, in the city of Fayetteville on 21 June 1947. He is buried in Cross Creek Cemetery in Fayetteville.

++++++++++

Weakley, Alan (2006) Carolina Eyebright and Mr. H.A. Rankin. North Carolina Botanical Garden Newsletter May-June 2006: 11.

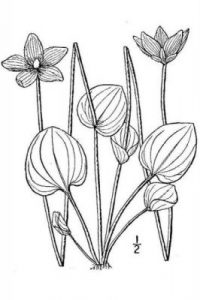

Grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia) – its white petals filigreed with a delicate tracery of green venation – is one of the most beautiful of North American and Eurasian wildflower genera. Yet one of the North American species of Parnassia remained a mystery for over 120 years, finally being solved through the efforts of a Fayetteville, NC, timberman named Hanry A. Rankin.

Rankin described himself in a letter to William Chambers Coker, founder of the UNC Herbarium: “I am not a botanist, but am much interested in the flora of the section.” This interest, as well as abundant opportunity to explore southeastern North Carolina while seeking stands of timber, made Rankin a distinguished figure in North Carolina botany. Two notable achievements were his discovery of a new species of Jessamine, named Gelsemium rankinii in his honor by John K. Small, and his rediscovery of Parnassia caroliniana.

Andre Michaux, French botanist (1746-1802), discovered and named Parnassia caroliniana from a vague locality in the Coastal Plain of “Carolina.” Through much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, taxonomists assumed that the locality was erroneous, because Parnassia was known as a circumboreal genus of cool habitats and its occurrence in the hot southern Coastal Plain seemed implausible. In 1928, though, Henry A. Rankin sent specimens collected near Hallsboro (Columbus County, NC) to Small at the New York Botanical Garden. Rankin was apparently not completely confident in the answer he received, as he wrote Coker on October 8, 1929:

Last fall I sent Dr. Small of the N.Y. Botanical Garden, specimens of Parnassia about which he became rather excited – said it was the original P. caroliniana found by Michaux on the Carolina coast and that the Northern plant going under that name was [a] different species – that it would now have to be called P. americana, Muhl. I have never seen the Northern species, and am sending you specimens from Hallsboro and would like to know – well I’m just wondering if perhaps he is a little too enthusiastic about multiplying species. Yours very sincerely, H.A. Rankin.

Two days later, Coker replied, assuring Rankin that his material represented the “real” P. caroliniana, expressing confidence in Small’s judgment and stating, “I am much pleased to get your specimen of the plant; it will prove a valuable addition to our herbarium.” He added, “I would like to get acquainted with you, and suggest that you take some opportunity to run up to Chapel Hill and see our herbarium and Arboretum. I would be much pleased to entertain you while in town” (a courtesy which we happily extend to our correspondents in 2006 as well). Thus began a fruitful correspondence and acquaintance that lasted at least into the mid-1940’s.

In 1934, Small’s colleague E.J. Alexander published a paper in the journal Addisonia in which he extensively quoted Rankin as follows:

That the Grass-of-Parnassus [which I sent] should turn out to be the true Carolina Grass-of-Parnassus is indeed good news and is received almost as a personal vindication, for I have always thought of it as that. Some years ago I found in Blanchan’s Wildflowers under Carolina Grass-of-Parnassus, the following – “What’s in a name, certainly our common Grass-of-Parnassus, which is no grass at all, never starred the meadows around about the home of the Muses, nor sought the steaming savannas of the Carolinas.”

I have always resented that passage as an almost personal affront. Owen Wister said in “The Virginian,” “When you call me that always smile,” and in this passage no smile is indicated.

What if our savannas are sometimes steaming, it is the condition necessary for the development for many wonderful plants which find here their most congenial surroundings.

But Grass-of-Parnassus does not star the meadows during the steaming season, instead, the “Eyebright,” its local name, times its first flowers to come just two weeks before frost… Its chosen habitat is the wet savannas and hundreds of acres may be seen liberally dotted with its white stars, but it finds its best development in the lower places, and here it almost covers the ground. Today, November 1st, it is in its prime and is the most conspicuous flower on many acres and in one little depression less than two feet in diameter I counted seventy-two flowers and buds.

Alas, with fire suppression, drainage, and development of outer Coastal Plain pinelands, few places bearing a resemblance to Rankin’s description remain. Parnassia caroliniana is an imperiled species, locally uncommon in a few counties of southeastern North Carolina and one county of the Florida Panhandle.

Thanks to the generosity of Rankin’s granddaughter, Dorothy Rankin, and the efforts of UNC Herbarium associate Bruce Sorrie, we recently received a large archive of Rankin’s correspondence, which promises to be a treasure trove of historical insights into botanical exploration of North Carolina’s Coastal Plain.