By Carol Ann McCormick, Curatrix, UNC Chapel Hill Herbarium

I have recently become very interested in a place I’ve never visited. It’s not a terribly exotic place, nor is it terribly far away — it’s just one of the many counties of The Old North State I have yet to explore. As is typical with me, a simple newsletter article about herbarium specimens experienced serious “mission creep” and expanded to include a fair dose of history and personalities.

Polk County is along the South Carolina border, and it is considered to be in the Foothills as the central and eastern portions lie in the Piedmont while the western portion is in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The highest point in Polk County is the summit of Tryon Peak (3,280 ft /1,000 m) and the lowest areas of the County are along the Green River (ca. 700 ft / 213 m).1 Polk County is named for William Polk (9 July 1758 – 14 January 1834) who was born in Mecklenberg County, North Carolina, was an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, served as the first president of the State Bank of North Carolina, and was a Trustee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1790-1834.2 However, note that Polk Place on the Chapel Hill campus is named in honor of James K. Polk, Carolina Class of 1818, 11th President of the United States, and first-cousin once-removed to William Polk.2,3

I was interested to learn if William Polk owned any enslaved people, as in 1818 he became an officer in the Raleigh Auxiliary of the American Colonization Society which sought to settle free African Americans in Liberia.2 “Both the Haitian Revolution [1791-1804] and Gabriel’s Rebellion [in Richmond, Virginia in the summer of 1800] prompted white leaders to take precautions to prevent a race war from breaking out…State legislatures and other leaders in white communities debated how to manage or remove the free Black population as they feared this group would inspire enslaved people to revolt and assist in their attempts to escape.”9

Through colonization, members of the American Colonization Society envisioned a future in which the free Black population would be settled in their own nation, eliminating an imminent threat to the institution of slavery. A few proponents of colonization initially suggested the creation of a colony for Black people west of the Mississippi or the West Indies. But after Paul Cuffe, a mixed race Quaker, ship builder, and activist, made a successful, self-financed trip with 38 Black people to Sierra Leone for the purpose of settling other free Black people in 1815, other supporters of colonization deemed the western coast of Africa the ideal location for a new colony. The perceived success of Cuffe’s voyage, along with the desire to remove free Black people from the United States altogether, served as the inspiration for the American Colonization Society. Originally known as the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Color of the United States, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded in 1816 by a group of white elites. ACS quickly recruited support and financial backing from enslavers, the Protestant and Presbyterian churches, and others, including the federal government officials. The members of ACS were an unusual mix of abolitionists and enslavers — two groups that typically opposed each other. While they had very different primary goals, they both felt that free Black people would never be accepted as equals in the United States. Abolitionist-leaning members believed it was an opportunity for African Americans to escape racism, start their lives anew, and form their own nation where they could enjoy liberation and citizenship. It also removed the challenges integration would place on white people. Pro-slavery supporters considered it a means to remove those who might threaten slavery. While members had many motivations for joining the ACS and different opinions on the issue of slavery, the underlying belief that whites and Black people could not peacefully co-exist in society held this unorthodox group together for decades. “In December [1821], the ACS purchased land along the West African coast for settlement and created the colony of [Liberia]. The capital in the colony was later named Monrovia in honor of [United States] President James Monroe, an ardent supporter of the ACS.”9

I asked Orange County Register of Deeds, Mark Chilton, if he had any information on whether William Polk was a slave owner. “I did a quick check of Mecklenburg County Deed Books from 1764 to 1779 and found a few deeds but nothing that connected him to slavery,” said Chilton. “The other place to look would be Wake County. I can check the published Wake Deed Book abstracts (which I have), but I believe a more comprehensive Slave Records Project for Wake County is currently under way and not completed… Polk’s will is at the State Archives in Raleigh, so a trip over there would probably also be revealing.”12 (I will have to save that bit of research for later, as I am writing this article over a holiday weekend, just days before it is due! )

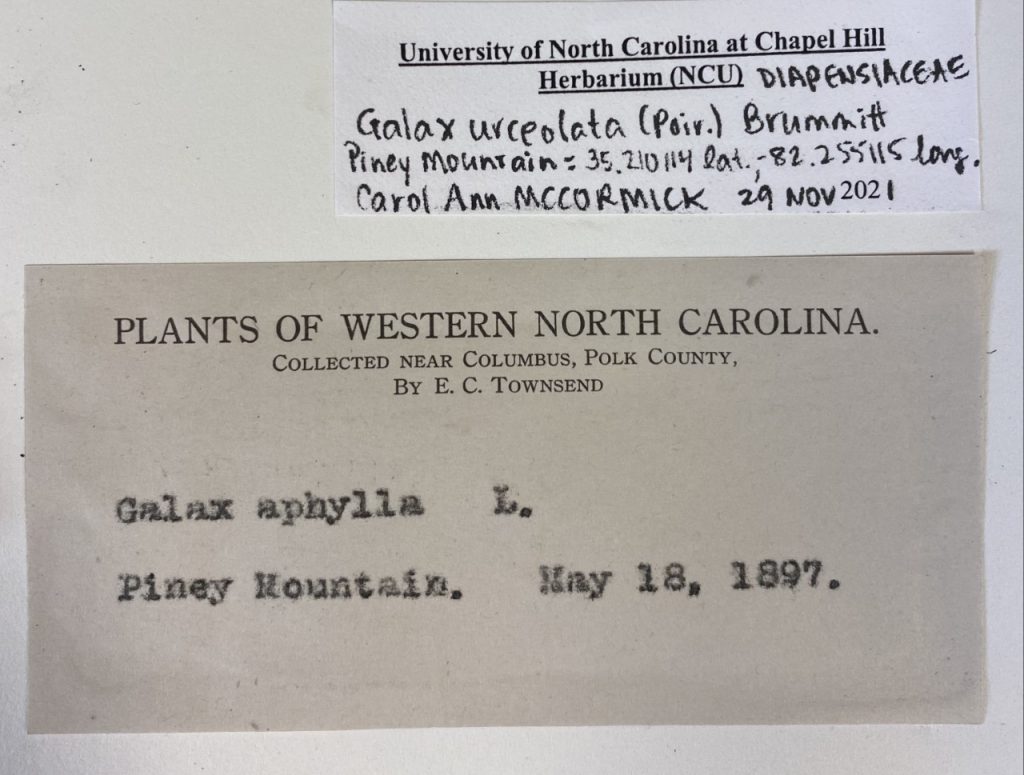

During the summer of 2021, the Liberty H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium (BH) of Cornell University asked if the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium

(NCU) would be interested in receiving as a gift about a hundred un-mounted specimens collected in Polk County ca. 1890-1900. “Most certainly!” was my reply, as this county is not well represented in our collection. By chance, we already had a good grasp of what specimens from Polk County are currently in our collection thanks to the work of Carolina undergraduate Akia Balfour. When Carolina students were sent home in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Akia continued to work for the Herbarium remotely by completing the database records for all our specimens collected in Polk County by using the digital images of the specimens on sernecportal.org.

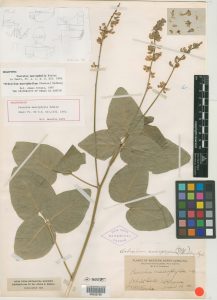

The box of specimens from Cornell University arrived in August 2021 and by mid-November, I found the time to begin mounting and accessioning them. All of the specimens were collected by E. C. Townsend, which was intriguing as Townsend and Rowlee collected bigleaf scurfpea (Orbexilum macrophyllum) in Polk County. “E.C. Townsend found this distinctive species in 1897 on the double peak of Tyron Mountain and White Oak Mountain in southwestern North Carolina and he collected it from that locale in 1899. It has not been found since. Several recent, unsuccessful attempts have been made to relocate it, and it is now believed extinct.“4 Alas, no specimens of bigleaf scurfpea were among the 2021 gift from BH.

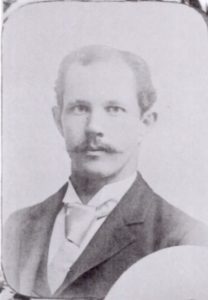

Aside from the connection to bigleaf scurfpea, I knew nothing about E. C. Townsend. The Herbarium had no specimens collected by Townsend. I was curious how Cornell University came to be in possession of plants collected in this remote area of North Carolina. My first task was to learn E. C. Townsend’s full name and to learn what he/she was doing in Polk County. I decided to start with the only other botanist I associate with Polk County: Donald Culross Peattie. Of the 1,260 specimens from Polk County curated by NCU, 805 were collected by Peattie. Between 1928 and 1931, Peattie published four installments of “Flora of the Tryon Region: An Annotated List of the Plants Growing Spontaneously in Polk County, North Carolina, and Adjacent Parts of South Carolina, in Greenville and Spartanburg Counties” in the Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society. In the first of these manuscripts, Peattie summarized prior botanical exploration of the area and noted the activities of Townsend. “The year 1897 was further remarkable for the advent of Mr. Edward C. Townsend, then of Cornell University, now of Olympia, Washington, who settled in Columbus [the county seat of Polk County] in January of that year and remained until December 1903. During his first four years especially he botanized extensively, amassing what must have been the largest and most interesting collection of plants ever taken in the county. Unfortunately his specimens have been divided among various institutions and often merged without record among their herbaria. I have examined all his specimens in the National Herbarium [US] at Washington, and most of those in Mr. Townsend’s own private collection, courteously forwarded to me. His non-duplicated types and the bulk of his collection are in the herbarium of Cornell University [BH], and some of his non-duplicated specimens have been verified for me by the kindness of Dr. Wiegand.”5

Having learned Townsend’s given name and found a connection to Cornell University, I contacted the Cornell University Library and received a veritable gold mine of information:

“Dear Carol Ann, Thank you for contacting Cornell’s Rare & Manuscript Collections (and hello to Chapel Hill from a UNC alumna :). We may even have met before; I took a tour of the Herbarium with one of my School of Information & Library Science classes!). Edward Candee Townsend was a student at Cornell between 1889 and 1894. He received a Bachelor of Arts in 1893, and then completed some graduate work in the 1893-1894 academic year [in Mathematics8], although he did not receive a graduate degree here. The 1931 Alumni Directory shows these details, and gives his address in Olympia [Washington State], where he was living by that point. His undergraduate thesis was titled “Systems of co-ordinates,” and he was Phi Beta Kappa. His alumni file lists his hometown as Lockport, New York. He was a merchant in North Carolina between 1898 and 1903; one of his daughters was born in Columbus in 1899, and the other in Lynn in 1902. By 1904 he was in Washington [State], where he worked as a draftsman with the U.S. Surveyor General, and then as an engineer with the State Land Department. An obituary in the alumni file (unclear which newspaper it was clipped from) states: “While in Polk County, North Carolina, he gathered an herbarium of the flora of that region. This collection has been written up in a monograph by the author and naturalist, Donald Culrose Peattie. A new variety of aster was named ‘Townsendii’ in his honor. He also collected plants from New York and Washington state. He had collections of wild flowers in Lockport, N.Y. high school, Cornell University, the National Herbarium at Washington, D.C., Washington State College at Pullman, and the University of Washington, Seattle.” Also included is a clipping from the April 4, 1937 edition of the Daily Olympian, regarding Townsend’s donation of a herbarium to Washington State University at Pullman, which Townsend forwarded to the Cornell Alumni Office with the note that the donation contained “basic collections at Ithaca and later additions.” A photo of Townsend is available in the 1893 Class Book. The Alumni News contains a few notes following his career after graduation. I hope that helps! Kate Carlin, Exhibitions and Public Services Assistant, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.”6

Next time I’m in Pullman, Washington I will have to visit the Washington State University Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections which curates the Edward Candee Townsend papers 1897-1937 which contains about 100 items “Correspondence and other papers concerning his botanical collecting in North Carolina and the donation of his herbarium to Washington State University”.7 Dr. Eric H. Roalson, Director of the Marion Ownbey Herbarium (WS) at Washington State University, says, “The WS Pacific Northwest collections are mostly databased (along with the University of Washington Herbarium (WTU) collection and other Pacific Northwest collections) on the Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria website ( https://www.pnwherbaria.org/data/search.php ). Doing a quick search, there are definitely collections of E. C. Townsend databased. There are some other Townsends in the database, so you might have to fiddle with the search terms, or filter out others of the same last name to whittle it down to what you want. Any of his collections not from the Pacific Northwest might not be databased yet, so those would have to be manually searched.”11

While NCU curates about 1200 vascular plant specimens from Polk County, other herbaria also have specimens collected there. North Carolina State University Herbarium (NCSC) curates 645 specimens from Polk County, and Duke University Herbarium (DUKE) curates 189 specimens. While these specimens do have digital images in sernecportal.org, the accompanying database records need completion to include collector’s name, date of collection, and detailed locality information. The Mecklenberg County Herbarium (UNCC) curates 248 specimens collected in Polk County. Many were collected by David Campbell between 2012 and 2018 as he inventoried the significant natural areas of the county.1 Converse College Herbarium (CONV) curates 259 specimens collected in Polk County, North Carolina. Dr. Doug Jensen, Curator of CONV (and Carolina alum!), says, “Most of our [Polk County] specimens are probably student collections. Polk County is close, and I’ve brought classes there. Pearson’s Falls is floristically diverse, but I don’t go there much because it’s privately owned [by the Tryon Garden Club]. Bradley Falls is a little further up the road, near Saluda, and I’ve been there a lot. It’s also quite dangerous! I’ve made a few collections there. One of my topo maps has a notation of a location for Asplenium pinnatifidum near Bradley Falls, but I never found the plants. We are (translate: I am) trying to get CONV more fully databased, but it’s a long and slow process.”10

As for the Edward Candee Townsend’s specimens gifted to NCU from BH, it will likely be January, 2022 before I get all of the specimens mounted, cataloged, imaged, and filed in the herbarium cases in Coker Hall. It is good to know that after a 125-year sojourn to the Empire State, these Polk County natives have returned home to The Old North State. When I ring in 2022, this verse from North Carolina’s Official Toast will have added meaning:13

Here’s to the land where the galax grows,

Where the rhododendron roseate glows;

Where soars Mount Mitchell’s summit great,

In the “Land of the Sky,” in the Old North State!

I have put Polk County, North Carolina on my “to visit in 2022” list, and I can assure you that if I re-find Orbexilum macrophyllum I will compose an Official Toast for Polk County which includes “Bigleaf Scurfpea” in at least one couplet!

SOURCES:

1. Campbell, David. 2018. An inventory of the significant natural areas of Polk County, North Carolina. Hendersonville, NC: Conserving Carolina.

2. Wikipedia contributors. “William Polk (colonel).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 Jul. 2021. Web. 27 Nov. 2021.

3. “Polk Place” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, June 2016. Web. 27 Nov. 2021. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/architecture/polk-place—s-new-classroom-b

4. “Orbexilum macrophyllum” NatureServe. 2021. NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. (Accessed: 27 Nov. 2021).

5. Peattie, D. C. 1928. Flora of the Tryon region of North and South Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 44(1): 95-125.

6. Personal communication, Carlin to McCormick via email, 27 October 2021.

7. Guide to Edward Candee Townsend Papers 1897-1937. Washington State University Libraries Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections. Pullman, Washington. http://ntserver1.wsulibs.wsu.edu/masc/finders/cg1588.htm#top

8. MATHEMATICS AT CORNELL: STORIES AND CHARACTERS, 1865—1965. (See page 127 for entry dealing with Edward Candee Townsend.) http://pi.math.cornell.edu/~lsc/Hist/histpart1.pdf . Accessed on 27 Nov. 2021

9. Robinson, Morgan. 2020. “The American Colonization Society”. The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-american-colonization-society Accessed on 27 November 2021

10. Personal communications, Jensen to McCormick via email, 23 November 2021.

11. Personal communication, Roalson to McCormick via email, 22 November 2021.

12. Personal communication, Chilton to McCormick via FaceBook Messenger, 28 November 2021.

13. Agan, Kelly. 2016. State Toast: The Old North State: A Toast (aka, The Tar Heel Toast). NCPEDIA. https://ncpedia.org/symbols/toast Accessed 30 November 2021.