Youngia japonica, an invasive species, in bloom.

By Carol Ann McCormick, Curatrix, UNC-Chapel Hill Herbarium

One of the problems with humans moving around the globe is that we bring other species with us. Sometimes plants or animals or microbes are intentionally introduced for food or medicine or companionship or beauty or nostalgia. However, many organisms are accidentally introduced as they may travel along with (or inside!) us. Alas, those organisms — whether intentionally or accidentally introduced — can spread to natural areas and become serious invasive pests.

One region’s treasure is another region’s terror

While I thoroughly enjoy seeing Carolina Anoles (Anolis carolinensis) sunning themselves on the walls of the the James & Delight Allen Education Center at the Botanical Garden, this species is a serious pest in Japan. Likely introduced via the pet trade or as a stow-away on military cargo in the mid-1960’s, the Carolina Anole is a competitor of native lizards. Many endemic insects on Ogasawara (the Bonin Islands) are on the brink of extinction due to the voracious appetite of the Carolina Anole.1

Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), a familiar robust plant native to North America, is an alien pest throughout Asia, Australia, and South America.2 Broomsedge (Andropogon virginicus) is native across the southeastern United States, but is known as the alien weed “Whisky Grass” in Australia as it was introduced to that continent after being used as packaging for bottles of American Whiskey.3 Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) “a long-lived perennial plant native to North America, [was] initially introduced as an ornamental plant to Shanghai in 1935, it then escaped into the wild and it is now spreading rapidly in China, especially in eastern China.”4

On specific epithets

The specific epithet — the second, non-capitalized word in a species name — can be a hint to the region of the world where the organism is native: caroliniana (of the Carolinas), virginicus (of Virginia), occidentalis (western), orientalis (eastern), americanus (of the Americas), europea (of Europe), sinensis (of China), antarcticus (of Antarctica), and japonica (of Japan) are just a few of the “geographical” specific epithets used. For some very rare organisms the specific epithet may be a very specific location: Plethodon cheoah, the Cheoah Bald Salamander, is restricted to Cheoah Bald and vicinity in Graham County and Swain County, North Carolina.5

I include a cautionary note about relying solely on a plant’s specific epithet to ascertain its native range. Our lovely native Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is a case in point.

“From the earliest days, this coarse plant with fragrant flowers, milky latex and stringy roots attracted much attention,” writes Erika E. Gaertner. “Its seeds were among the first sent from New France to Paris by Louis Hébert, a Frenchman regarded as the first Canadian pharmacist, farmer and settler in Stadacona (presently Quebec City, Canada).

Plants from these seeds were grown and later studied by Philip Cornut, a medical doctor and botanist. His treatise, Canadensium plantarium aliarumque nondum editarum Historia, published in 1635, is probably the first record on North American plants. Two of the present day milkweeds, Asclepias syriaca L. and A. incarnata L. are described. Cornut associated these plants with the dogbane of Asia Minor as described by Clusius, and identified Common Milkweed as Apocynum majus syriacum rectum … A hundred years later, the plant was collected by Clayton [John Clayton, 1694/5-1773, a botanist in Virginia] and classified by Gronovius (1739) in Flora Virginica as Asclepias erecta.

Linnaeus referred to both authors when he classified our Common Milkweed as A. syriaca L. in 1753. With the retention of the adjective syriaca of Cornut, he has puzzled many student of botany who have probably accused him of poor housekeeping because he did not know the provenance of the plants.” 14 Hemlock-parsley (Conioselinum chinense), also named by Linnaeus, is native to North America, not China as its specific epithet implies. “This is a Northern species, ranging from eastern Canada south to northern New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Iowa, and south only to one site each in the Mountains of Virginia and North Carolina.”6 I have been unable to find an explanation for this botanical-geographic snafu. I can only assume as Linnaeus named about 12,000 species of plants and animals, it is understandable that a few mistakes slipped in.

Youngia japonica: A rapidly spreading invasive species

One invasive plant whose explosive spread I have witnessed in the past 20 years is Youngia japonica. This weed in the Aster family has several common names, but most people I know simply call it Youngia. As its specific epithet hints, it is a native plant in Japan (and elsewhere in Asia). If you are not already acquainted with Youngia, I usually describe it as a dandelion on steroids — multiple flower heads on a tall hairy stem with a robust basal rosette of thinly textured leaves.

According to Phyllis L. Spurr’s treatment of Youngia in the Flora of North America there are about 30 species in the genus.7 I do not know why, when or how Youngia japonica was introduced to North America. The oldest herbarium specimen I’ve found from North America is curated by the Academy of Natural Sciences (PH). It was collected in 1929 by Oliver Myles Freeman in Montgomery County, Maryland “near the residence of E.A. Merritt, 1 mi NW of Chevy Chase Lake”.8 There may well be an older specimen which has yet to be fully cataloged — I doubt Youngia is high on any curator’s list of plants to be targeted for attention!

Youngia was first documented from North Carolina in 1958 by Harry E. Ahles, plant collector extraordinaire and co-author of the 1968 bible of southeastern plant biology, Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. Ahles’ field assistant and driver for the collecting trip to Pasquotank County was Ralph Page Ashworth, who was in the midst of his doctoral research in the Botany Department at Carolina after having earned his master’s degree from the Zoology Department in 1947. Ahles & Ashworth collected enough plants at “1.3 miles north of Knobbs Creek on US17-158 then 0.1 mile east (north of Elizabeth City)” to make at least six specimens: three are curated by NCU, while the others are at Florida Museum of Natural History (FLAS), the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT), and the University of South Florida (USF).8

In 1958 botanists, including Ahles, called this plant Crepis japonica (L.) Benth., but in 2003 our specimens were annotated by Phyllis L. Spurr to Youngia japonica (L.) de Candolle when she reviewed herbarium specimens for her treatment of the genus for Flora of North America.7 In 2013, Lowell Urbatsch et al. examined the specimen at FLAS and annotated it to Youngia thunbergiana DC., but recognizing this as a species distinct from Y. japonica is still controversial.7,9

Just who is “Young” commemorated (or, in my humble opinion, saddled) with the genus Youngia? “Le nouveau genre que je propose sous le nom d’Youngia, qui rappelle celui de deux Anglais célèbres, l’un comme poète, l’autre comme physicien…” wrote Alexandre Henri Gabriel de Cassini in 1831.10 According to Dr. Spurr, “the poet may have been Edward Young (also dramatist), 1683–1765; the physician may have been Thomas Young (also physicist and Egyptologist), 1773–1829.”7

Just as Youngia is not high on the list for cataloging, it is also not high on the list for collecting. When in a natural area I enjoy (and focus on) the native plants and try to ignore the weeds and litter infesting the margins of the parking lot. This year I resolve to Do Better — on both picking up litter and documenting weeds!

When the Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas was published in 1968, Youngia did not even get a map, as it had been documented only from Pasquotank County.11 It was next documented with an herbarium specimen in Orange County on March 20, 1974 by botany graduate student R. David Whetstone from “U.N.C.-Chapel Hill near Student Stores. Planter near the Pit.” By 1977 it had been reported from the Dismal Swamp in Gates County and from a plant nursery in Charlotte in Mecklenburg County.8 In the entry for Youngia in NC-Biodiversity.com, Sorrie & LeGrand note, “[There are] few records until the late 1990s, when it began an explosive expansion.”6

In the early 1990s, when I started seeing Youngia in more and more places, I put a call out to botanists to collect, press, and send specimens to the Herbarium in Chapel Hill. One botanist emailed me and said, “I read your email today and thought to myself that I have never seen Youngia in my area. But as I was doing the dishes, I looked out my kitchen window and saw some plants on the far side of the lawn — long stalks with with yellow flowers. Dang if it wasn’t Youngia in my own backyard and I’d never noticed them. Expect a package with some pressed plants in a couple of weeks.”

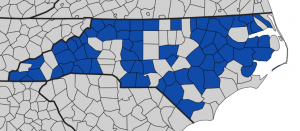

As of April, 2022 though Youngia has been documented with herbarium specimens from 32 counties in North Carolina, I’d be surprised if it is not actually growing in all 100 counties.

I challenge readers of the NCBG Newsletter to consult the map and list below. If you live in a county where Youngia japonica has not yet been documented (in dark blue), look for it! Suspect you have found Youngia thunbergiana? Collect it and send it in for botanists to study. Click here for “Pressing Matters,” a photo essay on how to collect, press, and send plant specimens to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium.

Youngia has not been documented with an herbarium specimen from these North Carolina counties: Alleghany, Anson, Ashe, Avery, Beaufort, Buncombe, Burke, Cabarrus, Camden, Chatham, Cherokee, Chowan, Clay, Cleveland, Columbus, Cumberland, Davidson, Davie, Duplin, Edgecombe, Forsyth, Franklin, Gates, Greene, Halifax, Henderson, Hertford, Hoke, Hyde, Johnston, Lee, Lenoir, Macon, Madison, Martin, McDowell, Mitchell, Montgomery, Nash, Northampton, Pamlico, Perquimans, Person, Pitt, Polk, Robeson, Rockingham, Rowan, Rutherford, Sampson, Scotland, Stanly, Stokes, Surry, Swain, Transylvania, Tyrrell, Union, Vance, Warren, Washington, Watauga, Wayne, Wilkes, Wilson, Yadkin, Yancey.

Notes & Sources:

- “Anolis carolinensis” Invasive Species of Japan. National Research and Devolopment Agency, Naitonal Insitutute for Environmental Studies. https://www.nies.go.jp/biodiversity/invasive/DB/detail/30100e.html accessed on 7 April 2022.

- “Phytolacca americana” Invasive Species of Japan. National Research and Devolopment Agency, Naitonal Insitutute for Environmental Studies. https://www.nies.go.jp/biodiversity/invasive/DB/detail/80030e.html accessed on 7 April 2022.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Andropogon virginicus.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 20 Mar. 2022. Web. 7 Apr. 2022.

- DONG Mei, LU Jian-Zhong, ZHANG Wen-Ju, CHEN Jia-Kuan, and LI Bo. 2006. Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis): An invasive alien weed rapidly spreading in China. J. Syst. Evol. 44 (1): 72-85.

- Petranka, J. W., S. Hall, and T. Howard, with contributions from H. LeGrand. 2022. Amphibians of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https://auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/amphibians/index.php.

- LeGrand, H., B. Sorrie, and T. Howard. 2022. Vascular Plants of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https://auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/flora/index.php.

- Spurr, Phyllis L. 2006. Youngia in Flora of North America, Volume 19: 255-256. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Data Portal. 2022. http//:sernecportal.org/index.php. Accessed on April 04.

- Urbatsch, Lowell E., John F. Pruski, and Kurt M. Neubig. 2013. Youngia thunbergiana (Crepidinae, Cichorieae, Asteraceae), a Species Overlooked in the North American Flora. Castanea 78 (4): 330-337.

- Cassini, Alexandre Henri Gabriel de . 1831. Annales de Sciences Naturelles (Paris) 23: 88.

- Radford, A. E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Rtichie Bell. 1968. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Edward Young.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 22 Oct. 2021. Web. 4 Apr. 2022.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Thomas Young (scientist).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 17 Mar. 2022. Web. 4 Apr. 2022.

- Gaertner, Erika E. 1979. The History and Use of Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.) Economic Botany 33 (2): 119-123.