By Carol Ann McCormick, Curatrix, UNC Chapel Hill Herbarium and Michael Lee, NCBG Data Scientist

With 800,000 botanical and mycological specimens (give or take) in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) how do we decide what to catalog? Of course our goal is to have every specimen cataloged, but it will take decades to make a complete database record (with collector’s name, when and where the plant was collected) for each wildflower, tree, fern, fungus, lichen, plant fossil, moss, and seaweed. We do completely catalog newly accessioned specimens as well as any specimen going out on loan. We may prioritize a genus or species for complete cataloging if a researcher or conservation organization needs the data. Other than that, my cataloging efforts are usually based on what my husband refers to as my “random walk through the herbarium.”

For example, I am reading a novel, Library at the End of the World by Felicity Hayes-McCoy. I cannot actually recommend this book — I find myself skimming paragraphs just to get on with it — but I’ll finish it just to find out what happens to the mildly engaging characters. Last night’s reading installment found Hanna and Brian walking through marram grass to watch seals on a beach in Ireland — which lead me to look up “marram grass” and to see if it occurs in North Carolina. As a result I’ll be completing the database records for Ammophila arenaria (European marrum grass) and Ammophila breviligulata (now called Calamagrostis breviligulata, American beach-grass) in coming weeks. In North Carolina, American beach-grass is found only on the Outer Banks and other barrier islands. “Native populations occur south to Oregon Inlet, and perhaps to Cape Hatteras; but its status southward is unclear, as it was extensively planted to stabilize dunes… As a sand stabilizer, American Beach-grass is known for its extensive rhizome system that links plants and holds sand from readily drifting.”2

Last week I happened to work on another grass, Erianthus giganteus, sugarcane plumegrass, because Mark and I found a clump on a walk near our house in Alamance County. It is an impressive plant — the flowering stalk of the one we found was 10+ feet high — and the only other herbarium specimen from Alamance County dated from 1956. So in the spirit of “document it once a century” we collected a flowering stalk and a leaf — now accessioned as specimens 678312 & 678313. I’ve completed the specimen records for all sugarcane plumegrass collected in North Carolina, and I’ll move on to cataloging our specimens from the rest of the Southeast this week.

Several years ago, I cataloged all NCU’s vascular plant specimens from Alamance County… because that’s where I live. I hoped to not only find places with good plants by looking at herbarium labels, but also to get a list of plants in need of documenting with collections. I also figured that could focus my botanizing efforts in places that had not already been explored. (Spoiler alert: that’s a lot of places in Alamance County!) I learned that 958 specimens had been collected in Alamance County between 1800 and 2000. Fully two-thirds of those specimens were collected during the summer & autumn of 1956, and only a few places in the county were visited during that year. I have wondered why Radford, Ahles, and Ramseur did not visit the most prominent topographic feature in the county — the Cane Creek Mountains. Hostile landowners seldom prevented Dr. Radford from exploring! The most botanized place was at Union Bridge (Old Greensboro Highway at the Haw River) about 11 miles west of Chapel Hill. Alas, when Union Bridge was replaced ca. 1995 the river bank was heavily disturbed.1 Dr. Radford visited Varnals Creek (sometimes called “Vernal Creek” on labels) several times. On April 10, 1956 he collected golden club (Orontium aquaticum) in Varnals Creek, the only time that plant has been documented in Alamance County. I would love to walk both sides of Varnals Creek from its confluence with the Haw River to its beginnings in the Cane Creek Mountains, and perhaps re-discover golden club and get a more precise location (latitude and longitude) thanks to my mobile phone. Harry Ahles botanized “along Cane Creek near junction with the Haw River” but never noted which Cane Creek. In an amazing lack of imagination there are two substantial creeks — one flowing in from the east and joining the Haw north of Union Bridge, the other flowing in from the west and joining the Haw just south of Union Bridge — with the same name. In the fall of 1956 George Ramseur was a graduate student and likely received some of his stipend for contributing to specimens to the Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. Ramseur botanized in Alamance County on the Caswell County border as well as on a route from Union Bridge to Snow Camp, north to Bellemont along NC 49, eastward to Swepsonville, then back to Chapel Hill via NC 54.

In 2020 after visits to Rocky Face Mountain and Little Joe Mountain, I got to work cataloging our ca. 800 vascular plant specimens collected in Alexander County, North Carolina. As a result of that effort, I learned that our earliest specimens from Alexander County date from the 1930s and were collected by interesting people such as Rev. Charles Edward Raynal and Dr. Solomon Wallace Hoffmann. To learn more about these Citizen Scientists, see “Following in Botanical Footsteps at Rocky Face Mountain“.

I chose to complete the catalog records for our specimens of Eriocaulon from North Carolina just because the plant is so darn cute. There are five species of “Hatpins” or “Pipewort” native to North Carolina: Eriocaulon aquaticum, E. compressum, E. decangulare, E. parkeri, and E. texense. Ten-angle pipewort (Eriocaulon decangulare) has been documented only once in Alexander County: “Bog, near southeast end of Rocky Face Mt., near springs” by Dr. Albert Radford and Laurie M. Stewart Radford in July 1940. I will have to explore that area of Rocky Face Mountain Recreation Area next time I visit to see if the bog and the pipewort have survived.

By the end of January 2023 most/all our vascular plant records for Person County will have been completed because undergraduate student Nathan Ross wanted to work remotely over the winter break. By completing database records for his home county, he will likely find some interesting places to hike and botanize this spring and exercise the plant identification skills he gained from taking Biology 272 Local Flora this past autumn with Dr. Alan Weakley and grad students Eric Ungberg and Brandon Fuller.

For the past few months, I have been starting each day by completing a dozen catalog records of Eleocharis (“Spikerush”) due to Scott Ward’s interest in these plants. “Eleocharis could often be

When a new student or volunteer starts in the Herbarium, we like to consult our database to see if they have a “birthday plant” — a specimen collected on the exact day and year of their birth. (A bonus point is given if the plant was collected on your birth date in your birth state; 2 points if in your birth county/parish.) In order to maximize one’s chances of finding a birthday plant, one can prioritize cataloging a plant that would be in bloom at that time of year. Those with November birthdays could prioritize witch hazel (Hamamelis), those with February birthdays could prioritize skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), and those with August birthdays could pick from a myriad of species in the aster family. Former Herbarium staffer and current volunteer Liane Salgado has an embarrassment of riches in the birthday plant department: three matching date, state, and county; nine matching date and state; and an additional 20 matching just date. I have personally targeted species likely to be collected in March (Claytonia–spring beauties, Hepatica, and Erythronium–trout lilies), so I consider it proof positive that Life Is Not Fair that I have yet to find a single plant specimen in the Chapel Hill Herbarium collected on my birthday. It is a small consolation that I have a birthday lichen: Alectoria sulcata collected by Katsuhiko Kondo in Iwaya-Kannonn, Oita Prefecture, Japan (alas, zero bonus points as I was not born in Japan).

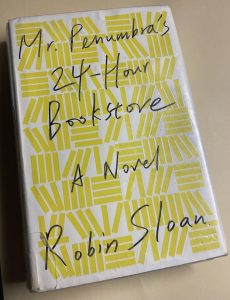

Since I opened this random walk with a book which I am currently reading but not recommending, I will close with a book I read a few years ago which I can highly recommend: Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan.3 I do not recall that it prompted me to database any particular plant species, but my husband is convinced that if one would map my random walk through the herbarium’s specimens — just as the protagonist in the bookstore maps the books purchased/borrowed by particular (and peculiar) customers — a great mystery will be revealed. Personally, I just hope to find a single birthday vascular plant of my own.

Since I opened this random walk with a book which I am currently reading but not recommending, I will close with a book I read a few years ago which I can highly recommend: Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan.3 I do not recall that it prompted me to database any particular plant species, but my husband is convinced that if one would map my random walk through the herbarium’s specimens — just as the protagonist in the bookstore maps the books purchased/borrowed by particular (and peculiar) customers — a great mystery will be revealed. Personally, I just hope to find a single birthday vascular plant of my own.

Find your birthday plant

Find plants collected on your birthday in the NCU Herbarium collection

DISCLAIMER: While the Herbarium is worldwide in scope, our databasing efforts in the vascular plant collection have focused on specimens collected in the Southeastern United States. We may well have a specimen from your year/state/county, but it has yet to be cataloged.

SOURCES & NOTES:

1. On a happier note, the new bridge construction included a great canoe access point on the Orange County side of the bridge, making the Haw River Paddle Trail from Saxapahaw to Union Bridge a very easy afternoon trip.

2. LeGrand, H., B. Sorrie, and T. Howard. 2023. Vascular Plants of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https://auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/flora/index.php.

3 I do recommend borrowing Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore out of the library as a hard-copy book instead of reading it on an electronic device. The cover has a hidden surprise which I discovered in the middle of the night.