by Gary Perlmutter, Lichenologist & University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium Associate

and Carol Ann McCormick, Curatrix of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium

Biologists tend to be list-makers. Amongst serious birders the number of species on their Life List — the birds seen or heard in person — is a matter of serious bragging rights. A conservation organization managing a piece of land for biodiversity needs to know the plants and animals and fungi and microorganisms which are found on the property — more lists. The zoologists and botanists of the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program gather and share information about rare plants and animals and natural communities across the entire state — many many more lists! In recent years checklists themselves have evolved, changing from published literature reports that document a snapshot of an estimated biota in space and time to a more dynamic form, published online and updated as new information becomes available.

Gary Perlmutter and Tom Howard are the people behind Lichens of North Carolina the one of the many “lists” available through the North Carolina Biodiversity Project (nc-biodiversity.com). “The NC Biodiversity Project is a private, nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote public interest in the state’s native species and ecosystems. Working in partnership with the NC Division of Parks and Recreation, our efforts focus on creating interactive websites that provide the public with both an accessible source of information on the state’s biodiversity as well as the opportunity to contribute new information of scientific and conservation value. Information compiled by these websites will help fill in our knowledge of the distributions, life histories, habitats, and other ecological associations of species, particularly as they exist in our state. We are especially interested in using these data to help guide efforts to conserve the state’s biodiversity. In order for those efforts to succeed, accurate and detailed knowledge of species’ conservation statuses within the state is required, as well as a broad base of public support for their preservation. Addressing these two needs are the most important goals of our project.” 1

Lichens are found in every county in North Carolina. Some species are widespread, while others have more limited ranges. Lichens are fascinating life forms, throwing out the convention of what we consider organisms through their dual or composite nature of symbiosis. With the combination of partners (fungal, algal, cyanobacteria, and others) and their often-unassuming nature, the biodiversity of lichens is a very active area of study. Field surveys combined with laboratory studies involving collected specimens in herbaria are finding more and more species. The North Carolina lichen checklist started with about 500 reported species in 2005 and has grown to about 1500 species over the past 18 years.2,3

In the past few months Gary Perlmutter has added three species to the list of lichens found in North Carolina. One was found by looking at old specimens. Another was found by looking more closely and critically at something that was taken for granted as simply algae. The third was found by looking to our neighbor, South Carolina, and wondering if a lichen found there could be found by exploring similar habitat just North of the Border.

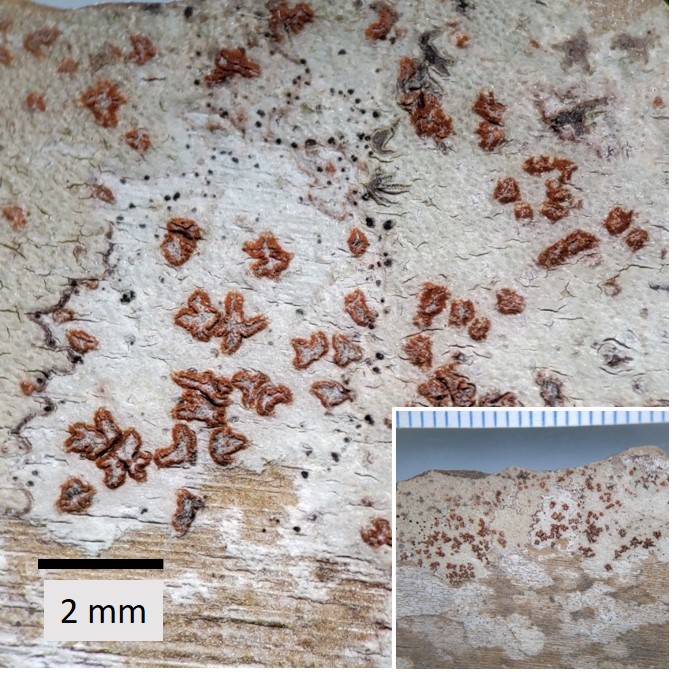

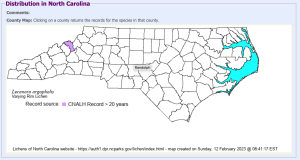

Lecanora argopholis (Ach.) Ach. “White Beaded Rim Lichen” was found in a search of the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria online specimen record repository commonly called Lichen Portal. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, along with about 170 other herbaria world-wide, catalog lichen specimens to this Consortium. By having specimens cataloged in a central place, one can search millions of specimens around the world from your home computer or smart phone. Gary found a single specimen of Lecanora argopholis collected by Paul Otto Schallert, M.D. on Roan Mountain, Mitchell County, in 1936 and deposited in the Field Museum of Natural History’s herbarium in Chicago, Illinois. Schallert originally identified it as L. frustulosa, a very similar species. Then in 2000, herbarium staff annotated the name to L. argopholis, and noted L. frustulosa as a synonym. However, a paper by Finnish lichenologist Heino Vänskä in 1984 clarified that the two names do represent different species, with L. frustulosa being yellowish and L. argopholis whitish in hue. The two species also differ in internal chemistry and have different spore shapes.4 “I was confused,” admits Gary. “Which lichen did Schallert really collect in 1936? I contacted the Field Museum to ask if they could re-examine the specimen to see which species it is. Lichenologist and expert on the genus Lecanora, Dr. Thorsten Lumbsch, examined the specimen and verified that it is L. argopholis.”

Lecanora argopholis is a saxicolous crustose lichen, meaning it is crust-like and grows on rocks. Its distribution is circumpolar and continental in the northern hemisphere (Eurasia and North America), reported as locally rare. Therefore, finding it in the high elevation areas of Roan Mountain is not surprising. A single specimen of L. frustulosa (“Yellow Beaded Rim Lichen”) is also recorded in Lichen Portal from the mountains of western North Carolina, and efforts are underway to verify its identity; if verified, this too would be a state record.

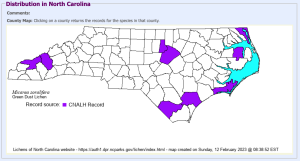

Micarea soralifera Guzow-Krzem., Czarnota, Łubek & Kukwa “Green Dust Lichen” was found during the New Hope Creek Biodiversity Survey, a year-long bioblitz conducted by the North Carolina Biodiversity Project for the County of Durham from September 2021 – August 2022. The New Hope Creek corridor is a gem of a natural area with mature bottomland forests in the growing metropolitan areas of Durham-Chapel Hill, through which Hwy 15-501 crosses. This survey recorded over 2000 different kinds of organisms: slime molds (Kingdom Protista); fungi and lichens (Kingdom Fungi); mosses, ferns, wildflowers, shrubs and trees (Kingdom Plantae); and tardigrades, spiders, millipedes and centipedes, insects and vertebrates including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals (Kindgom Animalia). The survey recorded just over 100 species of lichen, and 25 of those were county records. Most were county records for Durham, but some were county records for Orange, as parts of the New Hope Creek survey were in Hollow Rock Nature Park which spans both counties.

“Green Dust Lichen” too is a case of mistaken identity, but not with other lichens. With its green, fuzzy thallus covering tree bases, especially pines, it can be mistaken for free-living algae and thus overlooked in lichen surveys. It wasn’t even formally described until recently by a team of European scientists who found fertile material in Poland and the Czech Republic. 5 Then it was reported in the United States via an Indiana checklist published the following year.6

Micarea soralifera is named after the clumpy nature of the lichen thallus. This lichen reproduces primarily by vegetative means through dispersal organs termed soredia. Soredia are groups of algal cells wrapped by fungal hyphae, which then can be blown by the wind or brushed off by passing animals and land in a new area to grow as a new lichen. Soredia in this and many other species are themselves grouped in bodies termed soralia. Since the thallus of M. soralifera is composed of these soralia, the authors found it fitting to name it descriptively.

“I was totally unfamiliar with Green Dust Lichen,” said Gary. “When I saw it I thought it was just an alga, but I thought I saw some fungal hyphae too. So I sent it to Dr. James Lendemer, lichenologist at the New York Botanical Garden. I was half-expecting Lendemer to throw it back to me as an alga, so I was very happy when he identified it as a lichen. I checked Lichen Portal and learned that the New York Botanical Garden Herbarium (NY) has specimens of Micrarea soralifera collected between 2012 and 2020 from Carteret, Currituck, Columbus, Haywood, Pender, Swain and Tyrrell Counties in North Carolina. I went back and checked my unidentified lichen specimens and found that I’d collected it in 2009 from the Turnipseed Nature Preserve in Wake County! I added Green Dust Lichen to our list in Lichens North Carolina for the nine counties where it’s been documented, and I will be on the lookout for it elsewhere. It may well be more common than current maps suggest.” Gary’s specimens from the Mud Creek Bottomlands in Durham County and the Turnipseed Preserve in Wake County have been deposited in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium and are available to lichenologists for study.

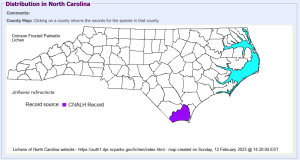

Arthonia rubrocincta G. Merr. ex Grube & Lendemer “Crimson Frosted Palmetto Lichen” is described as living in coastal habitats, restricted to living on the woody palm fronds of palmettos (Sabal palmetto) with a distribution in Florida and coastal Georgia.7 “I recall collecting this species on a planted palmetto near the Hilton hotel in North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, some years ago,” says Gary. “Thinking that palmettos could occur in North Carolina, I contacted park staff at Fort Fisher State Recreational Area in Brunswick County adjacent to South Carolina, to inquire if these iconic plants are there. Ranger Jeff Owen confirmed that a wild population of Sabal palmetto grows in the Bald Head State Natural Area — accessible only by driving on the beach for about 8 miles!”

“On a cold December day in 2022, I drove out to Fort Fisher State Recreation Area. Park staff were very accommodating — they drove me down the beach to Bald Head State Natural Area and dropped me off for my search. I saw palmettos growing just behind the dunes in what is termed Maritime Shrub Community (stunted tree subtype) according to the 4th Approximation of Natural Communities in North Carolina. 8 Zeroing in on the palmettos, I began searching with my handlens, and as I’d hoped, I found Arthonia rubrocincta! I collected specimens of the Crimson Frosted Palmetto Lichen and other lichen species I encountered. I was careful not to over-collect; I followed the ethic to collect only enough for vouchers and study, ensuring that the lichens are left to grow and persist in this harsh, exposed habitat.”

Back in the Herbarium in Chapel Hill Gary processed the material and identified 22 species, 10 of which are new records for Brunswick County. For perspective, scouring Lichen Portal for records from Bald Head Island (also known as Smith Island) yielded about 120 species overall. Most of these records were from areas to the west and south, including the maritime forests that are more sheltered than the coastal scrubs Gary explored in December 2022. It’s likely that Gary scored so many county records because he explored coastal scrub communities which had never been explored by lichenologists. “I had arranged with the park rangers to pick me up two hours after they’d dropped me off,” says Gary. “On the beach drive back, the park rangers told me lots of stories of people driving on the beach and getting stuck in the sand! I am grateful that Park staff were enthusiastic about helping me with my research so I did not suffer a similar fate.”

“What’s additionally interesting about Crimson Frosted Palmetto Lichen is that it actually belongs in related genus, not in Arthonia at all,” says Gary. “That report will be submitted for publication in a scientific journal, so stay tuned!”

SOURCES:

1. “About the NCBDP”. https://nc-biodiversity.com/ accessed on 12 February 2023.

2. Perlmutter, G.B. (2005) Lichen checklist for North Carolina, USA. Evansia 22(2): 51-77.

3. Perlmutter, G. and T. Howard. (2023) Lichens of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https://auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/lichen/index.php

4. Vänskä, H. (1984) The identity of the lichens Lecanora frustulosa and L. argopholis. Annales Botanici Fennici 21: 391-402.

5. Guzow-Krzemińska, B., P. Czarnota, A. Łubek & M. Kukwa. (2016) Micarea soralifera sp. nov., a new sorediate species in the M. prasina group. The Lichenologist 48(3): 161-169.

6. Lendemer, J.C. (2017) Lichens and allied fungi of the Indiana forest alliance ecoblitz area, Brown and Monroe counties, Indiana incorporated into a revised checklist for the state of Indiana. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 126(2): 129-152.

7. Grube, M. and J.C. Lendemer. (2009) Arthonia rubrocincta: belated validation of a name for a common species endemic to Sabal palmetto in the southeastern United States. Opuscula Philolichenum 7: 7-12.

8. Schafale, M. (2012) Guide to the Natural Communities of North Carolina: fourth approximation. North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 208 pp.