By Carol Ann McCormick, Curatrix, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU)

In a recent e-newsletter article Herbarium Associate Gary Perlmutter described finding Crimson Frosted Palmetto Lichen (Arthonia rubrocincta G. Merr. ex Grube & Lendemer) in Brunswick County, North Carolina. Gary concluded the article with, “What’s additionally interesting about Crimson Frosted Palmetto Lichen is that it actually belongs in a related genus, not in Arthonia at all. That report will be submitted for publication in a scientific journal, so stay tuned!”1

We did not have long to wait. On 28 March 2023, the lichen was transferred to the genus Coniocarpon and is now known as Coniocarpon rubrocinctum (G. Merr. ex Grube & Lendemer) Perlmutter, R. Miranda & Bungartz. Gary and his co-authors, Ricardo Miranda-Gonzalez (Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico) and Frank Bungartz (Arizona State University) published their findings in Phytotaxa 589 (3).

They note that while the original description of the lichen notes it “as being restricted to Florida and the Georgia coast on Sabal palmetto. Study of the present material increases the range of the species northward to the North Carolina coast and southeastward to Cat Island of the Bahamas in the Caribbean. We also provide evidence that this lichen grows on thatch palm, Coccothrinax argentata, which as has distribution similar to S. palmetto.”2

Two new lichens for Haywood County, North Carolina

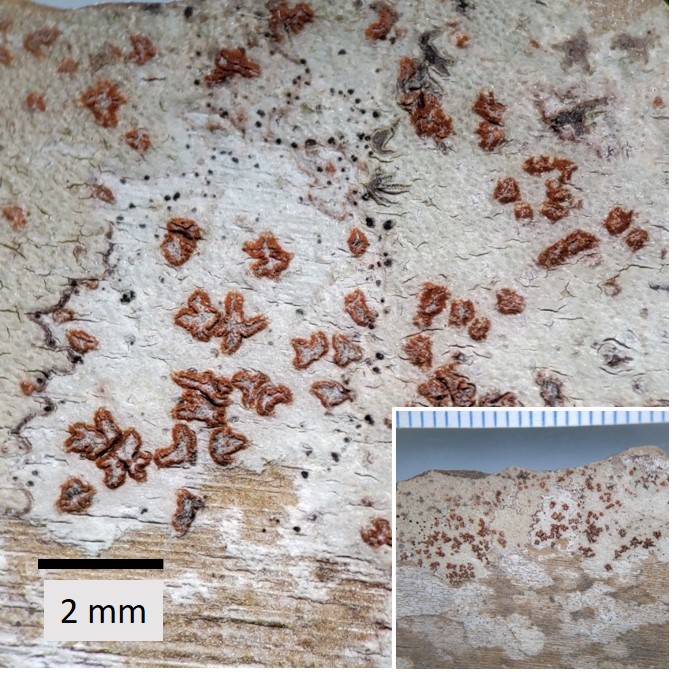

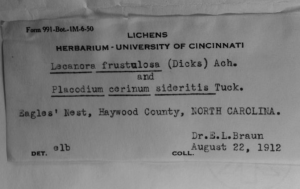

In that same recent e-newsletter article, Gary said, “A single specimen of Lecanora frustulosa (“Yellow Beaded Rim Lichen”) is also recorded in Lichen Portal from the mountains of western North Carolina, and efforts are underway to verify its identity; if verified, this too would be a state record.”1 The Herbarium in Chapel Hill borrowed the specimen from the University of Cincinnati Herbarium (CINC). The specimen had been collected by Dr. E. Lucy Braun from “Eagles’ Nest, Haywood County” on August 22, 1912. Gary notes, ”

The Lucy Braun specimen proved to be a mixed collection, containing two species she identified. The crust she identified as Lecanora frustulosa turned out to be Tephromela atra (“Black Eye Lichen”) with distinctive purple hymenium and golden hypothecium layers inside fruiting the bodies. The other crust, which Braun identified as Placodium cerinum sideritis (an orange lichen) instead turned out to be a Lecanora cenisia (“Smoky Rim Lichen”). Both these species are already in the North Carolina lichen checklist, but represent new records for Haywood County.” Gary annotated the specimen with the correct identifications, updated the species accounts and maps in the “Lichens of North Carolina” website, and returned the specimen to its home in Cincinnati.

Dr. Braun was inspired into a flurry of lichen collecting when she visited “Eagles’ Nest, Haywood County, North Carolina”. CINC curates 34 lichen specimens she collected on a single day — 22 August 1912 — including the specimen which Gary examined recently. Eaglenest Mountain (4925 feet; 35.4962070 latitude, -83.0431905 longitude) and adjacent North Eaglenest Mountain (5066 feet; 35.5002672 latitude, -83.0416956 longitude) are on Eaglenest Ridge, WSW of Lake Junaluska and NW of the city of Waynesville in Haywood County. North Eaglenest Mountain was formerly known as “Junaluska Mountain”, and one can find that name on older herbarium specimens.3,4

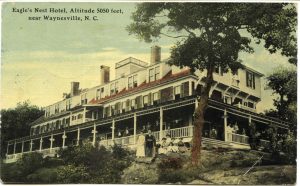

The Eagle Nest Hotel

I suspect that Dr. Braun stayed at the Eagle Nest Hotel while she was searching for lichens — I know I would have! “It was in 1879 that S. C. Satterthwait first came to Waynesville [Haywood County, North Carolina] from South Carolina by stage coach. He came to visit the White Sulphur Springs Hotel, but it was on this trip that he met his soon to be wife, Hester Ann Smathers. They married and in 1890 moved to Waynesville… A year later he bought a 204-acre tract on Junaluska Mountain (now known as Eagles Nest [sic; Eaglenest Mountain]) from W. H. Nichols.

In 1893, along with his brother in law George H. Smathers bought three more tracts on the mountain and acquired a 25-foot right-of-way from E. P. Hyatt, with the contract stating that the road would be finished by 1898. Various oral histories say that a groups [sic] of Cherokee Indians were hired to build the road to the top of the mountain. When large rocks were encountered, they would build fires and pour water on the rock to create fractures before busting them up. It’s said that the progress of the road could be measured by how high up the mountain the fires were located. Whether this is true or not, the 5-mile road was finished and open by the start of the 1898 tourist season. Many newspaper articles from that year mention the road and its unsurpassed views. The road was known as the “Graded Drive to the Eagle’s View” and by others “The Junaluska Drive.”

It appears that in 1899 Mr. Satterthwait started the construction of the 40-rooom hotel. It was to have three large stone chimneys, a dining room large enough to seat 100 guests and a roof-top observatory. The hotel opened July 24, 1900, and was handsomely furnished throughout. It attracted patrons from all over the country, especially during hay fever season when the hotel advertised “No Hay Fever at Eagle’s Nest Hotel” and added “No annoyance from children.” Over 1,000 guest stayed at the hotel in the 1903 season. It became so popular that Mr. Satterthwait added 10 rooms and tents along the ridge.

In a short time, Eagle’s Nest became a staple of Waynesville’s tourist industry, but with it’s [sic] great rise came a swift fall. Around 3 p.m. April 22, 1918 people in town noticed smoke coming from the hotel’s roof next to the observatory. Within minutes of the fire’s start, Clem Satterthwait Jr, his brother in law Ernest Withers, policeman Will Whitener and John Mull raced to the scene in Mr. Satterthwait’s car. However, by the time they reached the hotel, it was completely engulfed in flames. At 2,000 feet below, Waynesville was at a stand still as the children stopped playing and businessmen walked into the streets. Everyone watched as the flames leaped and great volumes of smoke poured from the tip of Mount Junaluska as if it was an erupting volcano.

Historian Bruce Briggs remembers this mother telling of the ashes falling into town. In the aftermath, the hotel was a total loss and the cause was never identified. The building was empty at the time, and it had been two weeks since the servants had built a fire there… For nearly 20 years after the fire, the Junaluska Drive road was only accessed by horseback and riding. Automobiles had not been allowed and by then the road had fallen into disrepair. It was in 1937 that H. G. Stone and H. L. Liner acquired the rights, improved the road and opened the “Scenic Eagle’s Nest Road.” A toll booth was installed just above the Piedmont Inn with a toll of $.50 cents per person in a car, and $.25 for pedestrians. The money collected was put back into improving the road. However this was a failing venture, the toll only lasted until 1941 and after the road became open for travel.

Over time the Satterthwait Estate was sold off by the heirs and houses were build on the majority of the lots. Riding to the top of the mountain and the old hotel site is still remembered by many of older locals. Bobby McKay often talked of the view from the rock and of bedsprings that were there in the 1950s… While walking along the ridge, the occasional piece of fine porcelain will catch one’s eye and the bedsprings, like the old hotel’s ghost, still watch over the town it help build.”5

Whether you are staying at a luxury inn on a mountaintop, enjoying a day hike along a trail, or simply enjoying a patch of open space near your house, keep an eye out for the myriad of lichens which live on tree bark, on rocks and on open ground.

SOURCES:

1. Perlmutter, Gary B. and Carol Ann McCormick. 2023. New Lichens in The Old North State. North Carolina Botanical Garden, March 2023 e-newsletter.

2. Perlmutter, Gary B., Ricardo Miranda-Gonzalea & Frank Bungartz. 2023. Placement of Arthonia rubrocincta in Coniocarpon (lichenized Ascomycota: Arthoniaceae), with an extended range for the species in southeastern North America and Caribbean. Phototaxa 589 (3): 278-282. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.589.3.6

3. North Eaglenest Mountain. GNIS ID: 1013987. https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/search/names/d6b47912-6f83-5c52-b861-853b8249041a/summary accessed on 28 March 2023.

4. Eaglenest Mountain GNIS ID: 1010966. https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/search/names/f71be044-ec17-5134-a313-df75cba6eadc/summary accessed on 28 March 2023.

5. McKay, Alex. 2018. Eagles Nest Hotel fire remembered at the tragedy’s centennial. The Mountaineer. April 23, 2018. https://www.themountaineer.com/news/eagles-nest-hotel-fire-remembered-at-the-tragedys-centennial/article_644caa6c-44d7-11e8-8b20-3f41a4dd889c.html accessed on 28 March 2023.