By Carol Ann McCormick, Curatrix, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU)

On the last Sunday in October, 2022, my husband suggested we take a walk at Weymouth Woods Sandhills Nature Preserve in Moore County, North Carolina. From our home in southern Alamance County it is a very pleasant 1.25 hour drive, made even more pleasant by the day’s cool temperature and vibrant autumn colors of the deciduous trees lining each roadside. I knew Mark’s quarry was Pine Barrens Gentian (Gentiana autumnalis L.), but we left that wish unspoken lest we jinx our chances of seeing it.

The Sandhills was a riot of Asters, and thanks to Bruce Sorrie’s excellent book, A Field Guide to the Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region (available in the NCBG Garden Shop!), we were able to identify most of them. One of my favorites was Walter’s Aster (Symphyotrichum walteri (Alexander) Nesom). The flowers of Walter’s Aster are large, with long pale blue or blue-violet ray flowers and yellow disc flowers. The leaves are what really caught my attention: they are tiny, triangular, and reflexed or folded downward against the stem. Walter’s Aster is “locally common in Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris) habitats in the Sandhills and in the southern Coastal Plain counties [of North Carolina]. In a variety of moisture settings, but usually in diverse and well-managed Longleaf Pine stands,” says Bruce Sorrie.1 By “well-managed” Sorrie means using prescribed fire and not raking pinestraw from the woodland. Overall, the forests of Weymouth Woods are burned every three years. However, according to Park Superintendent Billy Hartness, the area which harbors the greatest display of Walter’s Aster was in past years burned annually. Clearly Walter’s Aster is a pyrophile!

“So who was Walter,” asked Mark, “and what did he do to deserve getting such an awesome plant named after him?” Wikipedia provides a concise summary of Walter’s life. “[Thomas] Walter was born in Hampshire, England, around 1740. Little is known of his family background or early life. He evidently received a good education but no details are available. Sometime before 1769 he arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, where he worked as a merchant. He later acquired a rice plantation on the Santee River where he lived the rest of his life. He became interested in botany and undertook a detailed plant survey within a fifty-mile radius of his home [in Berkeley County, South Carolina], collecting seeds for his garden and building an extensive herbarium. Based on this effort, Walter completed a manuscript in 1787 containing a summary of all the flowering plants species found in the region. [Flora Caroliniana by Thomas Walter] was the first comprehensive regional flora set in eastern North Carolina and the first to use Linnaeus’ binomial naming conventions. Walter gave the manuscript to fellow botanist John Fraser who took it to England and arranged for its publication in 1788. Flora Caroliniana provided brief Latin descriptions for over 1,000 plant species in 435 genera. Walter is credited with the discovery of 200 new species and four new genera. Today, 88 of these species and one genus (Amsonia) still bear the valid names provided by Walter in his Flora. Walter died on 17 January 1789, shortly after the publication of his flora. His herbarium was taken to England by Fraser and eventually purchased by the British Museum of Natural History [BM] where it still exists. Since his death, eight plant species [including Walter’s Aster] have been named in his honor.”2

About fifteen years ago I found an herbarium specimen of Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneiodes L.) bearing the rather strange locality, “Hanging over the tomb of Thomas Walter, St. John’s Parish.” The specimen had been collected on 29 August, 1909 by the founder of the Herbarium and first chair of the Botany Department at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Dr. William Chambers Coker. Since that time I have been on the lookout for other specimens collected by Coker (or others) at Thomas Walter’s grave. In 2017, Herbarium Intern Hannah Medford systematically went through the Herbarium searching for specimens which Coker collected at or near the location. The guide for Ms. Medford’s search was Coker himself — or rather a wonderful paper entitled “A Visit to the Grave of Thomas Walter” which he published in 1910 in the Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society.3 Ms. Medford read Coker’s paper closely, noted each plant that he mentions, and then searched our herbarium for plants collected by him on the 29th of August, 1909, or as he wrote in pencil on most labels, “Aug 29-09.” Ms. Medford’s search yielded a total of 43 specimens. As we continue to catalog our collection it may be that we find additional specimens Coker collected on his pilgrimage, as perhaps he collected plants which he did not mention in his manuscript.

In the “they don’t write ’em like this anymore” department, Coker’s paper is part geneology, part travelogue, part botany, part history, and all nostalgia. I also find it interesting that we are as removed from Coker’s pilgrimage (1909 to 2023: 114 years) as he was from Walter’s death (1789 to 1909: 120 years). I will let Coker speak for himself by quoting extensively from his paper.

Thomas Walter’s legacy is an example of the issues we face when we talk about the foundational botanists in our region. Some of the original botanists working in the Carolinas were plantation owners at a time when that meant they enslaved thousands of individuals, and their wealth and power was built on that enforced labor. The excerpt below from the founder of the Botany Department at UNC-Chapel Hill, William Chambers Coker, himself the descendent of plantation owners and enslavers, reveals that the plantation economy was still viewed in a rosy light in the 1910’s. Cotton is mentioned as the savior of lowland South Carolina, and only passing mention is made of the “five thousand negro slaves [sic]”, much less the tens of thousands of enslaved families before and after, whose unpaid labor supported the wealth of the Walter, Marion, and Coker families.

#####

Excerpts From ‘A Visit to the Grave of Thomas Walter’ by William Chambers Coker

I have long felt a “motion of love” to see the spot where Thomas Walter lived and died, and as nothing had been heard of the condition of the place for several years I took an opportunity in August of last year [29 August 1909] and carried out the long planned trip.

Arriving at St. Stevens from Charleston [South Carolina] in the evening I made arrangements with Mr. W. F. Boykin for a conveyance [saddled horses], and made an early start with him the next morning for Pineville, six miles away. The road passed through flat, sandy, pine woods, an occasional low bog, and much good farming land. Close at hand towards the north stretched the broad swamp of the Santee river, five miles wide in places. In the old days before the [American] Revolution when the up country was still an untouched wilderness this swamp was cleared and cultivated in corn and indigo for a distance of at least 10 miles west of St. Stevens. Within this swamp at that time were five thousand negro slaves, and on the low bluffs along the southern edge of the swamp there were scattered the comfortable dwellings of the planters. Here wealth and refinement established themselves, and upper St. Stevens and St. John’s became the seat of one of the most cultivated and prosperous societies of the state. Now is all changed. The dark days began by the breaking upon the people of the frightful storm of the revolution. No other part of the country suffered more from the ravages of a destructive war. The internecine character of the struggle is well illustrated by the fact that after the battle of Black Mingo Charles and Thomas Peyre, the brothers of the wife of Thomas Walter, were captured as tories by General Francis Marion — a near neighbor — and sent on foot to be jailed in Philadelphia. The suffering of Marion’s men are well known, the misfortunes of the Tories were equally severe.

Impoverished by the war the planter’s families found little hope before them. The loss of England’s bounty of sixpence a pound on indigo put an end almost immediately to the planting of that crop; and to add to the miseries of the people the Santee river, about 1790, began to be subject to disastrous floods that destroyed the magnificent crops of the rich swamps and drove the planters to give them up once more to the wilderness. They have never again been cleared.

The introduction of cotton as a profitable crop by the invention of the saw gin in 1794 was a most timely and present help in trouble, and saved the country from complete impoverishment. A large number of fine plantations along the south side of the Santee from St. Steven’s to Eutawville soon gained a fair measure of prosperity. Until about 1794 the proprietors lived on their plantations throughout the year, but after that they got together and established the town of Pineville where they built their summer houses. At the time of its greatest prosperity the village contained about 60 houses, supported a fine academy, and was the center of a community that reflected all that was the best of simplicity, hospitality and culture in southern life before the [American Civil] war.

When I passed through the village on that Sunday morning last August no trace was to be seen of the life of the old days. But three or four houses remained — remained only to mark the backward swing of the inconstant pendulum of time.

From Pineville we drove on to the club-house of the Oakland Gun Club, where we ate our lunch and with fresh horses took to the saddle for the remaining distance. After about a mile through the barrens we came to Belle Isle, one of the old plantations of the Marion family. In a fine grove at the end of an avenue stands the old house, with smoke house and kitchen of substantial brick in the rear. It is difficulty to imagine a more depressing spectacle than the one that met us here. The house, once the focus of the abounding life and hospitality of a famous estate, is now fast falling into ruin. The steps are gone, the ceiling of the piazza is down at one end, and the roof broken through in several places. As I entered the house and picked my way over the insecure floor to its dark central passage I was startled by the sudden falling of clouds of bats that squeaked and circled above me.

About one hundred feet west of the house is the old family burying ground. Here are the graves of General Francis Marion and his wife…

Moving on to the west from Belle Isle we passed a few fields cultivated by negroes and were soon in the heart of as wild a country as is to be found in the state. Broad stretches of thick pine woods, dense canebrakes and impenetrable bogs surrounded us, and to the north extended for miles the great, deep swamp of the Santee. Here is the paradise of wild things… deer… bear, turkey and wild cats…

After covering almost four miles more we arrived at the old Santee Canal, finished in 1800, at an immense cost… now passing through an almost trackless forest and abandoned to decay. The massive masonry work of the locks of this canal is of brick that is said to have been imported from England. The remarkable preservation of much of this masonry after the ravages of over a entry of neglect is an evidence of the thoroughness and honest workmanship that was characteristic of the times.

On examining one of the most perfect of these locks there was noted on the east wall a thick fringe of the exotic-looking fern, Pteris serrulata, a native of China that is now naturalized in the extreme southern states. This is, I believe, the farthest north that it has been found. The only other fern on the lock was the ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron). On the west wall as an equally luxurient mass of the very attractive southern vine, Decumaria barbara. This vine is characteristic of the coastal region. It extends up as far as Darlington County [South Carolina], but does not quite reach Hartsville [Coker’s hometown].

The horses were urged through the water and sticky mud of the canal with difficulty and passing on for a short distance we came suddenly to a clearing where the trees had recently been logged. The river current sweeping through the swamp towards the south presses up here to the front of some high bluffs…

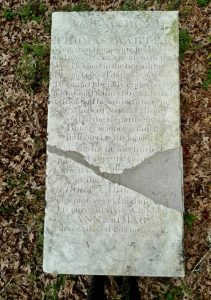

Mr. Boykin went off to the south to find [our guide], who finally arrived and led me a half a mile farther up the river which had again bent away into the swamp. Here about one hundred feed from the edge of the swamp are standing two fine old willow oaks and at the foot of one of these is the grave of Thomas Walter. It is covered with a flat stone, now broken in two and though dotted with lichens and stained and corroded by time the inscription may still be deciphered… I give it below just as it appears on the stone:

In Memory of THOMAS WALTER Native of Hampshire in England and many years a resident of this State. He died in the beginning of the year 1788 aetatis cir. 48 ann [at about the age of 48]. To a mind liberally endowed by nature and refined by a liberal education he added a taste to the study of Natural History and in the department of Botany science is much indebted to his labors. At his desire he was buried on this spot once the garden in which were cultivated most of the plants of his FLORA CAROLINIANA. From motive of filial affection his only surviving Children ANN and MARY have placed this memorial.

It was hard to believe that on this spot was one of the first Botanical gardens of America, planted and tended with loving care by the man who lay at our feet; that in this deserted place was kindled one of the first fires on the alter [sic] of Science in the new world.

I looked about me for those traces of the garden that Ravenel had mentioned more than fifty years ago. Not one remained. No Stellingia [sic; Stillingia sylvatica] or any other thing except the wildest growth of forest. Leaning over the grave wast the southern buckthorn (Bumelia lyciodes [now Sideroxylon lycioides]), deciduous holly (Ilex decidua), arrow wood (Viburnum dentatum) and red ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica). From their branches hung Virginia Creeper (Ampelopsis quinquefolia [now Parthenocissus quinquefolia]), poison ivy (Rhus radicans), Carolina moonseed (Cebatha Carolina [now Cocculus carolinus]), Cat-brier (Smilax Bona-nox) and Trachelospermum difforme, a vine that was discovered by Walter himself.

#####

In more recent times South Carolina botanists have made their own pilgrimages to Thomas Walter’s grave. On March 30, 2021 a groups of South Carolina botanists made their own pilgrimage to Thomas Walter’s grave and posted photos from the excursion on Face Book. “What a privilege to visit the grave of a founding father of South Carolina botany: Thomas Walter! And even better to be with Dr. Richard Porcher (a relative of Walter!), and Dr. John Nelson. A great day of botany and history, including visiting the north end of the old Santee Canal and the remaining locks,” wrote Keith Bradley, botanist with South Carolina Heritage Trust on the Face Book post.

The site of Thomas Walter’s grave is privately owned but has a conservation easement owned by the Lord Berkeley Conservation Trust funded by the South Carolina Conservation Bank. “Founded in 1992, Lord Berkeley Conservation Trust works to protect the land in the Santee River and Cooper River watersheds, the Ashley River headwaters, and Four Holes Swamp. To date, Lord Berkeley Conservation Trust has protected over 40,000 acres permanently through easements and acquisitions.” According to the SC Conservation Bank website, “The Old Santee Canal (OSC) property is situated on the Santee River with 1.9 miles of scenic river frontage. Its high bluffs overlook the Santee and provide stunning views both from the river and land side…Thomas Walter’s gravesite is also located within the property.”7

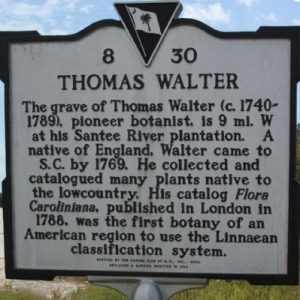

If you are traveling to South Carolina and find yourself near the village of Saint Stephen in Berkeley County, be on the lookout for a historical marker devoted to Thomas Walter erected in 2003 by the Garden Club of South Carolina. The marker is located at the intersection of US 52 and Colonel Mamham Drive (33° 26.33′ N, 79° 59.1′ W).5

To learn more about Thomas Walter I recommend two resources: Thomas Walter and his plants: the life and works of a pioneer American botanist by Daniel B. Ward (published in 2017 by the New York Botanical Garden) and Thomas Walter Carolina Botanist by David H. Rembert (published in 1980 by the South Carolina Museum Commission).

In March 2023 Botanical Garden staff had a chance to visit Historic Stagville in Durham County. Stagville was one of the largest plantations in North Carolina, and its holdings included what we know as Penny’s Bend Natural Area managed by the Garden. Vera Cecelski , the site director of Historic Stagville, led us through the grounds, weaving together the stories of the landowners and the stories of the thousands of enslaved people who tilled the land, cared for the livestock, built the homes and barns, and served in the landowner’s home. It’s well worth a visit if you want to delve deeper into history of the land protected by the North Carolina Botanical Garden.

To bring this Walk with (Thomas) Walter and William (Chambers Coker) to its end, I’m sure you’ll be glad to know that Mark did indeed find Pine Barrens Gentian in bloom on our October 2022 walk in Weymouth Woods!

SOURCES:

1. LeGrand, H., B. Sorrie, and T. Howard. 2023. Vascular Plants of North Carolina [Internet]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Biodiversity Project and North Carolina State Parks. Available from https://auth1.dpr.ncparks.gov/flora/index.php

2. Wikipedia contributors. “Thomas Walter (botanist).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 20 Apr. 2022. Web. 30 Oct. 2022.

3. Coker, William Chambers. 1910. A visit to the grave of Thomas Walter. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 26 (1): 31-42. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/jncas/id/1095

4. Rembert, David H. 1980. Thomas Walter Carolina Botanist. Museum Bulletin Number 5: South Carolina Museum Commission, Columbia, South Carolina.

5. “Thomas Walter” The Historical Marker Database. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=39003 accessed on 23 Jan 2023.

6. Lord Berkeley Conservation Trust. https://www.lordberkeley.org/ accessed on 23 Jan 2023.

7. “Old Santee Canal” South Carolina Conservation Bank. https://sccbank.sc.gov/old-santee-canal accessed on 23 Jan 2023.