by R. Kevan Schoonover McClelland, doctoral student, Department of Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

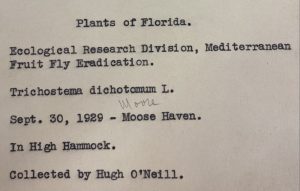

One Wednesday afternoon, I was going through my specimens of blue curls (Trichostema sp.) that I had borrowed from the Florida Museum of

Natural History (FLAS) in Gainesville, Florida for my doctoral thesis on the taxonomy of this genus, when I came across an interesting collection locality: Moose Haven. Given that these particular specimens were collected in Florida, I was thoroughly confused. My confusion was shared by a prior, anonymous, researcher who had penciled on one of the labels “probably Moore Haven!” a town on the southwestern coast of Lake Okeechobee in Florida (specifically Glades County). However, this only added to my confusion, since blue curls do not typically occur in that region of Florida. “Strike one against Moore Haven as a collection locality,” I thought.

Perhaps during the Pleistocene, moose (Alces) roamed Florida along with Glyptodonts (Glyptotherium), Giant Armadillo (Holmesina), Mastodons (Mammut), and Giant Ground Sloths (Eremotherium, Megalonyx, and Paramylodon) and a treasure-trove of fossilized moose gave rise to this intriguing place name. Perhaps an extensive clan of people with the surname Moose named their settlement after themselves. Perhaps Moose Haven was a corruption of the original Timacua or Seminole name for that place.

Before going off on even more moose-related tangents, I examined the other information presented on the specimens. The plants were collected by Hugh O’Neill on September 30, 1929. The labels have the curious heading “Ecological Research Division, Mediterranean Fruit Fly Eradication.” To find out more, I did what many researchers do when they want to quickly search for something: I consulted Google.

I first looked into the fruit fly eradication. It turns out that in 1929 and 1930, there was an infestation of Mediterranean Fruit Fly (Ceratitis capitata) in northern and central Florida. The “Med fly” is “one of the world’s most destructive fruit pests. The species originated in sub-Saharan

Africa and is not known to be established in the continental United States. When it has been detected in Florida, California, and Texas each infestation necessitated intensive and massive eradication and detection procedures so that the pest did not become established… Because of its wide distribution over the world, its ability to tolerate cooler climates better than most other species of tropical fruit flies, and its wide range of hosts, it is ranked first among economically important fruit fly species. Its larvae feed and develop on many deciduous, subtropical, and tropical fruits and some vegetables. Although it may be a major pest of citrus, often it is a more serious pest of some deciduous fruits, such as peach, pear, and apple. The larvae feed upon the pulp of host fruits, sometimes tunneling through it and eventually reducing the whole to a juicy, inedible mass.”1 There would seem to be no reason for the collector be in Glades County, well south of the Med fly infestation. Strike two for the Moore Haven hypothesis!

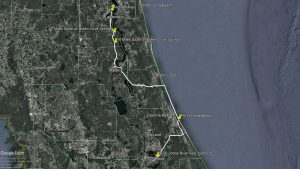

To find out more about Hugh O’Neill and his plant collections, I went to SERNEC (Southeast Regional Network of Expertise and Collections), a searchable database of herbarium specimens from across North America.3 By searching on the collector’s name, then sorting those results by date, I found that Hugh O’Neill had been all over Florida (but not Glades County) in the summer and fall of 1929 and that he had collected hundreds of specimens. Interestingly, some of the herbarium labels were signed “Rev. Hugh O’Neill.” On the day that the blue curls were collected, September 30, 1929, O’Neill had been in Port Orange, Sanford, and just south of Green Cove Springs, Florida. These towns are in Clay and Volusia County, making a collection in Glades County, at the other end of the state, highly unlikely. Strike three for the Moore Haven hypothesis!

So, what or where is Moose Haven? Google had a rather surprising answer. Moosehaven is a retirement community in Orange Park, Clay

County, Florida, founded in 1922 by the Loyal Order of Moose, a fraternal organization whose mission is to care for the young and the old. Moosehaven is a sister campus to Mooseheart, which was established in 1913 as a residential living community for children just outside of Chicago, Illinois. Since children and older people need different things in their living communities, the Loyal Order of Moose created Moosehaven in Florida to find “a home in a warmer climate for the aged members [of the order] and their spouses… Supreme Secretary Rodney H. Brandon purchased the historic four-story Hotel Marion and its eight acres, located on the St. Johns River in Orange Park, Florida. He named the property Moosehaven and the new residents renamed the hotel, Brandon Hall. By 1926, there were 144 residents. Known initially as the City of Endeavor, Moosehaven residents performed all of their own work and operated a successful dairy and farm. At various times, as many as 500 Moose members resided at Moosehaven.” 4 I have concluded that Moose Haven on the Rev. Hugh O’Neill’s labels is indeed Moosehaven in Clay County, as that fits best not only with the range of Trichostema dichotomum in Florida, but also with O’Neill’s collecting route during late September, 1929. Was Rev. O’Neill a member of the Loyal Order of Moose, did he happen to have friends who lived there, or was it just a good place to botanize? These questions remain unanswered.

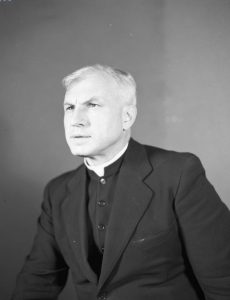

Throughout this process, my interest in Rev. Hugh O’Neill deepened. Who was this clergyman who traveled all over Florida, seemingly on a mission to eradicate an infestation of fruit pests? This was slightly more difficult to determine. Eventually I came across my Rosetta Stone: a newspaper article from 1930 titled “Priest Botanist Protects Florida from Fruit Fly.”5 Everything finally fell into place! Between the article and further searches (now armed with more concrete information) I was able to determine the following:

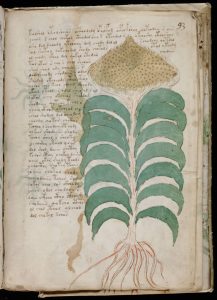

“A native of Allentown, Pa., [The Rev. Hugh Thomas O’Neill (1894-1969)] was ordained a priest in 1920 after studying at St. Leo’s Seminary in Tampa Fla. He was graduated from the University of Florida and joined Catholic University in 1930 after being awarded a doctorate there. In 1929, he surveyed Florida for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s bureau of plant quarantine, studying the eradication of the Mediterranean fruit fly.”6 When he joined Catholic University he also became the curator of their herbarium (LCU). He mentored numerous Ph.D. and Masters students in botany during his years there.7 “He [also] served as a botanist on two U.S. expeditions, to the Bahamas in 1933 and to Guatamala and Honduras in 1936.”6 O’Neill identified illustrations of plants from the Voynich Manuscript (a 15th century Italian manuscript with cryptic writing and botanically inspired

illustrations) as new world species, specifically a pepper plant and a sunflower.8,9 His obituary describes him as “an authority on sedges, Antarctic vegetation and the interpretation of vegetation from aerial photographs” as well as an “accomplished cellist.”6 He retired from his roles at Catholic University in 1956.7

Unfortunately, my search for O’Neill’s report describing his findings from the Med Fly expedition mentioned in the newspaper article turned up nothing. Before I return the Trichostema specimens to the Florida Museum of Natural History I will annotate those bearing the collecting locality Moose Haven with a succinct but clear statement on the correct spelling (Moosehaven), and its location (latitude 30.16901°, longitude -81.698283° +/-500 meters) in Clay County, Florida. Perhaps next time I find myself in northeastern Florida I will make a pilgrimage to Moosehaven, as the community still exists on the banks of the St. Johns River, and see if I can find any Trichostema dichotomum growing there nine decades after Rev. O’Neill collected it.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) curates at least seven specimens collected by Rev. O’Neill, but only one of these is possibly from the Med Fly project, and alas, none are blue curls.

SOURCES & NOTES:

1. Thomas, M.C., J.B. Heppner, R.E. Woodruff, H.V. Weems, G.J. Steck, and T.R. Fasulo. Featured Creatures: Mediterranean Fruit Fly. Originally published as Department of Plant Industry Entomology Circulars 4, 230 and 273. Publication Number: EENY-214. September, 2010. https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/fruit/mediterranean_fruit_fly.htm accessed on 22 July 2021.

2. Image modified by R. Kevan Schoonover McClelland July 2021 from Incidence of the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann), in Florida, 1929-1998. Drawing by G.J. Steck and B.D. Sutton, Division of Plant Industry. https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/fruit/mediterranean_fruit_fly.htm accessed on 22 July 2021.

3. Data Portal. 2021. http//:sernecportal.org/index.php. Accessed on July 22.

4. Moosehaven: History. https://www.moosehaven.org/history/ accessed on 22 July 2021.

5. Anonymous. 1930 Feb 15. Botanist Priest Protects Florida from Fruit Fly. Guardian. Page 4 (col. 1-2). [retrieved from Newspaper Archive of Arkansas Catholic, Little Rock, Arkansas]. http://arc.stparchive.com/Archive/ARC/ARC02151930p04.php accessed on 22 July 2021

6. Anonymous. 1969 Mar 08. Fr. Hugh O’Neill: Professor of Botany at Catholic U. Washington Post, Times Herald. Sec. B4. [retrieved from ProQuest]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/147721683?pq-origsite=summon accessed on 22 July 2021

7. Tucker, Arthur O., et al. 1989. History of the LCU Herbarium, 1895-1986. Taxon 38(2): 196-203. [retrieved from JSTOR]. www.jstor.org/stable/1220834 accessed on 22 July 2021

8. O’Neill, Hugh. 1944. Botanical Observations on the Voynich MS. Speculum 19(1): 126. [retrieved from The University of Chicago Press Journals]. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.2307/2856859 accessed on 22 July 2021

9. Sunflower: Voynich Manuscript 93r. Yale University Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/ciencia/esp_ciencia_manuscrito07e.htm accessed on 22 July 2021