by Corbin T. Bryan1, Dan Meyers2, Van Cotter3 and Carol Ann McCormick4

New plants, animals and fungi are not only found in far-away exotic locations. The Carolina campus might be a surprising place to find a fungus never before documented from North Carolina, but recently a Carolina Biology major did just that.

In mid-December Corbin Bryan was coming to campus to drop off some fungi he had collected over the autumn and noted scores of red-capped fungi fruiting abundantly in the mulched beds adjacent to Coker Hall. He plucked a few and brought them to the fungal lab to share with fellow Carolina undergrad Dan Meyers and with Herbarium Associate Dr. Van Cotter. Together they came up with a tentative identification of Leratiomyces ceres (“Chip Cherry” or “Redlead Roundhead”), a potential new species of mushroom for North Carolina.

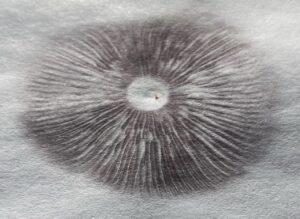

As several other mushroom species resemble L. ceres, the fungal team carried out several chemical and microscopic diagnostic tests before they could be sure of its identity. One step was to mount the spores on a glass slide and view them with a microscope under 1000x magnification. The mushroom’s elliptical, thick-walled spores and other microscopic features supported the team’s identification. Next, they exposed the mushroom’s cap to a solution containing lye (potassium hydroxide, KOH) to see if the mushroom changed color. Color changes under KOH are often important to distinguish among closely related species. KOH caused the mushroom’s cap to change from red to a deep gray-purple color, consistent with L. ceres. Another diagnostic step was to make a spore print, by placing the mushroom cap gill-side-down on a sheet of paper, covering the cap on the paper with a bowl so it is not disturbed by air

currents, then waiting overnight or a few days until the spores have dropped onto the paper. The mushroom’s spores were dark purple-brown — more support for the team’s identification as L. ceres.

The fungal collection of the Herbarium in Chapel Hill, along with 133 other herbaria around the world, is available online for researchers or interested amateurs via mycoportal.org. Checking this database revealed no specimens of L. ceres from North Carolina in our collection or in any of the other herbaria. While Dr. Cotter was searching mycoportal, Corbin and Dan

checked iNaturalist, a citizen-science website, and found eleven previous reports of L. ceres from North Carolina. However most (perhaps all) of the iNaturalist sightings were misidentified and are various other mushroom species. Moreover, none of the iNaturalist reports were supported with vouchered specimens in an herbarium, so Corbin’s collection is the first verifiable report of the Chip Cherry fungus from The Old North State.5

How long has L. ceres been present in the beds around Coker Hall? We don’t know! Corbin noted it on 16 December 2020, but perhaps it has been there in previous years. Dr. William Chambers Coker (1872-1953), for whom Coker Hall and Coker Arboretum are named, was an eminent mycologist and prolific collector of fungi in and around Chapel Hill, and if L. ceres had been common in the area he certainly would have collected it!6

How was the Chip Cherry mushroom introduced into North Carolina? Again, we don’t know! The fungus was first described from Melbourne Australia in 1888 under the name “Agaricus (Psilocybe) ceres.” Since then it has been a globe trotter, first showing up on the west coast of North America probably after 1951, in Europe during the 1950s and in North Carolina circa 2020!

As its common name implies, it is usually found in wood chips or mulch. So where does the mulch in the beds around Coker Hall come from? We did not know, but in this case, we knew whom to ask! Herbarium Curator Carol Ann McCormick called in University Forest Manager Tom Bythell and he in turn called upon his colleague, Dwayne McLaurin, who makes the mulch for campus plantings. Within minutes of calling the Grounds Department, Tom and Dwayne arrived to tell us more than we ever dreamed was possible to know about the mulch in the two areas around Coker Hall. First — and most important for the question of how the fungus got to Coker Hall — all the mulch is locally sourced. All the trees and brush from University properties are collected and brought to a central mulching site at Carolina North. Dwayne examined the mulch around Coker Hall and found pieces of Tulip Poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) as well as Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana), but said without doubt

other tree and shrub wood is in the mix as well. When had the mulch been applied? The area with the most prolific growth of L. ceres on the south side of Coker Hall was likely mulched around graduation — or, as Dwayne corrected himself, “what should have been graduation time at Carolina, May or maybe early June,” and the mulch was rather coarse, having been ground up only once. The mulch on the west side of Coker Hall was of finer texture having been ground up twice and had been applied at least two years ago, perhaps longer. Tom and Dwayne encouraged Van and Dan to join them on a “field trip” to the Carolina North facility to see if L. ceres could be found in the Mother Mulch Pile. Alas, no L. ceres at Carolina North, but Tom and Dwayne promised to keep an eye out for any bright red mushrooms in mulch around campus and to notify the Herbarium.

Dr. Coker would be pleased that Carolina undergraduates are still making great mycological discoveries on the campus he knew and loved. Thanks to Dr. Cotter, students and Garden members interested in mycology have an able and enthusiastic mentor.

In April, 2021 the North Carolina Botanical Garden will host the Mid-Atlantic States Mycological Conference featuring scientific talks and posters. Due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the conference will be online. For registration information, contact Dr. Van Cotter (hvtcotter@gmail.com).

Cap of Leratiomyces ceres after application of KOH; note the color change. Photo by Corbin Bryan, December 2020.

- Corbin T. Bryan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Class of 2022, is majoring in Biology and German. He is from Durham in Durham County, North Carolina.

- Dan Meyers, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Class of 2021, is majoring in Biology and minoring in Chemistry & Entrepreneurship. He has been the Mary McKee Felton Intern in the Herbarium since 2018. He is from Holly Springs in Wake County, North Carolina.

- Van Cotter, Ph.D., has been an Herbarium Associate since 2014 and also volunteers his expertise to the mycological herbaria at Duke University and North Carolina State University. Dr. Cotter lives in Raleigh, Wake County, North Carolina.

- Carol Ann McCormick is the Curatrix of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has been a staff member of NCBG since 1992, and lives in Thompson Township, Alamance County, North Carolina.

- Corbin Bryan’s state record collection of Leratiomyces ceres is cataloged in mycoporal.org, catalog # NCU-F-0031728 .

- McCormick, Carol Ann. 2013. The manure piles of Chapel Hill. North Carolina Botanical Garden Newsletter, December 2013, page 11. http://www.herbarium.unc.edu/newsletter2008TOpresentCUT_files/2013112Manure.pdf