By Carol Ann McCormick, Curator, UNC-Chapel Hill Herbarium

A few weeks ago, Herbarium director Alan Weakley and I received an email from a colleague in Virginia offering some plant specimens for the Herbarium. “It’s a small batch of interesting taxa, mostly things out of a personal herbarium I’ve kept over the years. I plan to distribute the rest of it to various institutional herbaria over the next few years, so I could potentially have quite a bit more for you if you all are interested,” wrote Gary Fleming.

Indeed we are interested! Mr. Fleming is a senior vegetation ecologist with the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Natural Heritage Program and has conducted inventories of natural communities across Virginia since the early 1990s. A box of 35 pressed, dried vascular plant specimens arrived in the Herbarium in mid-March and after two weeks quarantine in the freezer to kill any unwanted insect pests, I opened the box.

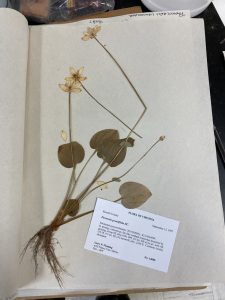

What a treat! Each plant was in a fold of newsprint, with a label tucked in with the plant. There were 35 plants in all; the collection of Carex cristatella, “crested sedge,” had enough material for two herbarium sheets, bringing the total of accessioned material to 36 herbarium sheets. Most, including the crested sedge, are on the rare list for Virginia1, but the one that caught my eye was a particularly lovely specimen of Parnassia grandifolia, or large-leaved grass-of-Parnassus.

Parnassia is “a genus of 15-70 species, herbs, primarily of arctic and north temperate areas. Our species (especially P. caroliniana) are among the most southerly of the genus in distribution. Parnassia (all species) are among the most beautiful of our native plants. From a distance the white flowers are attractive but not extraordinary; when observed closely, though, the delicate tracery of the green veins on the waxy white petals is astonishing.”2 Apparently all-around naturalist Scott Ranger was as puzzled as me as to why this lovely wildflower has not only a Greek mountain in its name but also “grass” despite having distinctly non-grasslike foliage. “Almost everything about the name of this plant is enigmatic! Grass-of-parnassus is certainly not a grass and it doesn’t grow on Mount Parnassus. The genus name seems to come from Ancient Greek Παρνασσός Parnassos, the name of the son the nymph Kleodora and the human Kleopompus. His city was flooded so they moved it up on the slopes of the mountain that took his name becoming Mount Parnassus. This mountain was sacred to Apollo and home to the Muses. The literary world considers it the home of poetry. This persistent, yet unsubstantiated, story persists: “Parnassia is a reference to Mount Parnassus; Linnæus applied the name to the genus based on an account in Materia Medica, a written work by the Greek physician Dioscorides (Dioscorides called it Agrostis En Parnasso)”. Linnæus makes no mention of the origin of the name in Species Plantarum and clearly used a pre-existing name. Agrostis comes from the Ancient Greek ἄγρωστις agrōstis, a kind of grass now the genus of bentgrass and the connection to Dioscorides is thin at best. Today Parnassia is not found on Mount Parnassus but “Parnassia palustris… [is found on], Mt Tzena [in] Northern Greece.” Plantlife, a conservation organization in Great Britain, makes this unsubstantiated claim: “The cattle on Mount Parnassus developed a taste for the plant; hence it was an ‘honorary grass.'”3

One important mission of the Herbarium is to document rare plants. “I am often asked why a Natural Heritage botanist or ecologist collects specimens of rare plants. After all, if these species are rare, wouldn’t the act of collecting be detrimental to the population?” writes Mr. Fleming. “The answer to the second question is that my colleagues and I do not make collections that threaten the viability of a native plant population, even those that are not “rare.” Populations of one-to-few individuals are

off-limits. Even in larger populations, certain collecting techniques such as leaving the roots or collecting only one stem of a branched plant can further reduce impacts. However, it may surprise people to learn that although some species are rare at a larger geographic scale, they often form large populations in their discrete, favored habitats. The removal of one plant from a population of hundreds or thousands is sustainable in these cases.

The purpose of collecting plant specimens is so that they can be permanently archived in an herbarium. Properly preserved herbarium specimens can provide researchers with invaluable taxonomic, biogeographical, and ecological data long after the collections are made. Herbaria are essential in allowing original material to be re-evaluated as taxonomic concepts and classifications change over time. In addition, the information on specimen labels provides much information about the geographic distribution and habitats of a taxon. One of the primary reasons I collect specimens is to populate the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora, which maps the county distribution of all vascular plants and bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, and hornworts) in Virginia. In addition, my colleagues and I have used herbarium specimens to assist in relocating historical populations of rare species, or to locate potentially special habitats and plant communities. The advent of SERNEC.org and other online herbarium databases has opened up many new possibilities for these kinds of research and made the process easier and more efficient.

The collections I consult most are those with large Virginia holdings: George Mason University Ted R. Bradley Herbarium (GMUF), the Virginia Tech Massey Herbarium (VPI), The College of William and Mary Herbarium (WILLI), the Longwood University Harvill-Stevens Herbarium (FARM), the Lynchburg University Ramsey-Freer Herbarium (LYN), the University of Richmond Herbarium (URV), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU), the Smithsonian United States National Herbarium (US), and Harvard University’s Gray Herbarium (GH). Most of my personal collections have been deposited at the Virginia institutions, with whose curators I have had long-term collegial relationships.”

We look forward to receiving more beautiful specimens collected throughout Virginia by Gary Fleming!

Specimens received from Gary Fleming, March 2021 and accessioned into NCU:

Acanthaceae Dicliptera brachiata “branched foldwing”

Alismataceae Echinodorus cordifolius “creeping burhead”

Asteraceae Iva annua var. annua “annual marsh-elder”

Senecio suaveolens “sweet Indian-plantain”

Solidago lancifolia “lanceleaf goldenrod”

Solidago tortifolia “twistleaf goldenrod”

Boraginaceae Lithospermum latifolium “American stoneseed”

Cyperaceae Carex conjuncta “soft fox sedge”

Carex cristatella “crested sedge”

Carex crus-corvi “ravenfoot sedge”

Carex davisii “Davis’ sedge”

Carex flava “yellow sedge”

Carex lupuliformis “false hop sedge”

Carex manhartii “Manhart’s sedge”

Scleria verticillata “low nutrush”

Euphorbiaceae Acalypha deamii “Deam’s threeseed”

Fabaceae Acmispon helleri “Carolina prairie-trefoil”

Hydrophyllaceae Phacelia covillei “Coville’s phacelia”

Lamiaceae Blephilia hirsuta “hairy woodmint”

Mosla dianthera * “miniature beefsteak-plant”

Pycnanthemum setosum “awned mountain-mint”

Pycnanthemum torreyi “Torrey’s mountain-mint”

Pycnanthemum virginianum “Virginia mountain-mint”

Syndandra hispidula “Guyandotte beauty”

Limnanthaceae Floerkea proserpinacoides “false mermaid-weed”

Orobanchaceae Pedicularis lanceolata “swamp lousewort”

Parnassiaceae Parnassia grandifolia “largeleaf grass-of-Parnassus”

Poaceae Amphicarpum amphicarpon “pinebarrens peanut-grass”

Melica nitens “three-flowered melicgrass”

Muhlenbergia capillaris “hair-awn muhly”

Oplismenus undulatifolius * “wavyleaf basketgrass”

Poa paludigena “bog bluegrass”

Sporobolus compositus “tall dropseed”

Ranunculaceae Hydrastis canadensis “goldenseal”

Santalaceae Pyrularia pubera “buffalo-nut”

*noxious weed

SOURCES:

1. Townsend, John F., 2020. Natural Heritage Resources of Virginia: Rare Plants. Natural Heritage Rare Species Lists (2020-Winter). Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond, Virginia. 9 pp. plus rare species lists and appendices. https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural-heritage/document/plantlistdec2020.pdf

2. Weakley, Alan S. 2012. Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States, Working Draft of 30 November 2012. University of North Carolina Herbarium, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

3. Ranger, L. Scott. “Parnassia asarifolia Ventenat 1804, grass-of-parnassus.” Scott Ranger’s Nature Notes [online blog]. http://www.scottranger.com/parnassia-asarifolia-grass-of-parnassus.html accessed 1 April 2021.