I moved to Chapel Hill and started working at NCBG in December 1991. I had a one year contract, funded by a grant from the Institute for Museum & Library Services (IMLS), to inventory the vascular plants of Nature Trail Hill, the Coker Pinetum, and Stillhouse Bottom. I spent the winter laying out grid systems and 20×50 meter plots to ensure that I gathered information from all the plant communities within those natural areas. All spring I had a nagging feeling that something was missing. As I was enjoying an afternoon break, sprawling on the sunny forest floor, listening to upland chorus frogs and enjoying a thermos of hot tea and gingersnap cookies, I finally realized what was missing from this vernal landscape: skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus).

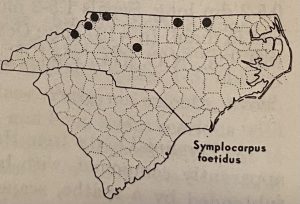

Skunk cabbage is a familiar sight to anyone who tramps around wet woods in northeastern North America. Despite its common name, it is not related to cabbage — it is in the Araceae family along with Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum). Because skunk cabbage was the very first plant to bloom in the spring, it was a highlight of nature walks I did at my previous job as a naturalist at Bowman’s Hill Wildflower Preserve in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. As I sipped tea and crunched on gingersnaps I consulted my constant companion in the field, Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas by Radford, Ahles & Bell (1968) and was stunned to realize that skunk cabbage is quite rare in North Carolina (only seven counties, along the Virginia border or in the mountains) and absent from South Carolina.

Why do I like skunk cabbage so much? Basically because it is a weird, ugly plant! As both its common name and scientific name indicate, the leaves do exude a distinctly skunky odor when torn or bruised. It’s an odd looking plant — the flowers are on the ground and appear well before the leaves. “Skunk cabbage flowers do not have the appearance of a typical flower,” note Barbara Nicholson and Sylvia Halkin. “The outer covering of the inflorescence consists of a thick, pigmented bract (called a spathe) with an opening on one side. The interior of the inflorescence has a bulbous fleshy spike called a spadix, crowded with minute petal-less flowers. Flowers of the skunk cabbage are perfect, having both male and female reproductive parts.” But here’s where skunk cabbage gets really cool… or should I say hot. “Members of the plant family Araceae, including skunk cabbage, have evolved the ability to metabolically generate considerable quantities of heat… If the spathe is covered by snow during this period, it can melt right through the snow. The skunk cabbage has an underground stem that stores large quantities of starch. During heat production, starch is translocated to the flower where it is metabolized at a high rate, generating the heat. This heat, besides keeping the flower from freezing, is thought to attract, shelter, delay, and reward pollinators. It is also believed that the heat assists in the diffusion of carbon dioxide and the skunky odors produced by the plant. Various pollinators are attracted to both the heat and the odor.”1

What pollinators are attracted to skunk cabbage? A study in a bog in Québec, Canada found that the flowering period “ranged from 15 to 20 days, with, chronologically, a female phase of about 5 days, a bisexual phase of 2 days, and a male phase of 9 days…The air inside the floral chamber was warmed by the heating spadix, particularly during the female phase (~ 6°C warmer than ambient air)… Pollination is probably generalist considering the large variety of Coleoptera [beetle] and Diptera [fly] families attracted to the plant such as Chronomidae [lake flies3], Sphaeroceridae [lesser dung flies or lesser corpse flies4 ], Mycetophilidae [fungus gnats5], Phoridae [coffin flies6], Drosophilidae [fruit flies], Chloropidae [grass flies7], and Anthomyiidae [root-maggots8].” 2 A good project for a budding pollination ecologist would be to discover what insects pollinate skunk cabbage in the Piedmont of North Carolina, as I would imagine that there are substantial differences in the insects present in North Carolina and Québec.

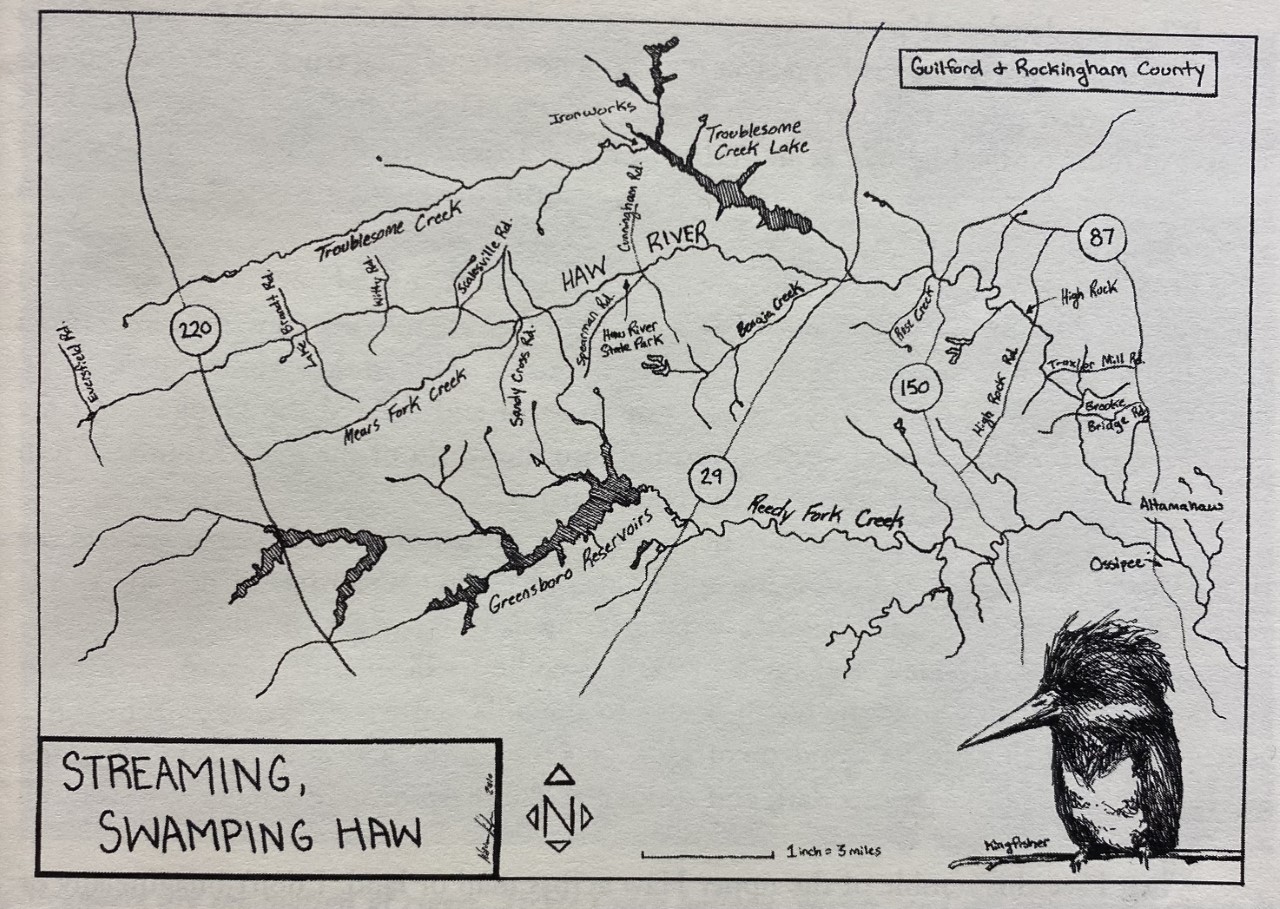

In 2011, my husband and I joined friends for dinner and Dr. Sonke Johnsen, a biologist at Duke University, mentioned he had contributed photographs to Down Along the Haw, the History of a North Carolina River by Elon University professor emerita Dr. Anne Cassebaum.9 As we live in Alamance County within walking distance of the Haw River, I purchased the book for my husband’s birthday that year. As I read her descriptions of exploring the wetlands of the headwaters of the Haw River in Guilford and Forsyth Counties I was surprised that she listed skunk cabbage as one of the interesting plants she’d found. She and Ken Bridle, stewardship director of Piedmont Land Conservancy, directed me to a wetland and heron rookery on Mears Fork, a tributary of the Haw River. After nearly two decades of absence I was able to see skunk cabbage again.

In the spring of 2021, Illinois Natural Heritage botanist Susan McIntyre visited the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium. She wanted to examine herbarium specimens of the plants she’d be seeking during the coming field season when she returned to the Land of Lincoln. We chatted about good places to botanize in the area, and went on several hikes together. In one of our many emails that spring, she casually mentioned that she’d seen skunk cabbage along Lake Townsend just north of Greensboro. Like me in 1991, she was not aware that this plant is rather rare in the Piedmont. She provided excellent directions (on the Blue Heron Trail, north shore of Lake Townsend, between the trail and the lakeshore, along the first creek E of Church Street bridge), and not only was I able to see skunk cabbage again, but also I discovered another destination for hiking and botanizing.

“Lake Townsend, named in honor of James R. Townsend, City Manager of Greensboro from 1947-1961, is the largest of Greensboro’s municipal reservoirs. The lake is 1,542 acres and is adjacent to the Bryan Park Complex and Golf Course off Highway 29 North. The lake was built and open for recreation in 1969.”10 There are a plethora of trails to explore. The Lake Townsend Loop Trail is 8.7 miles long and I have hiked only small portions of it, so I’ve got lots more to explore. (Be prepared to share the trail with mountain bikers, and keep your dog leashed!) I will have to explore the four miles of trails in the Richardson-Taylor Preserve (68 Plainfield Road, Greensboro) overlooking the extensive wetlands of Long Branch, as in February 2022 we could only manage a quick visit, and it seems a likely spot for more skunk cabbage.

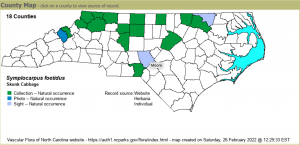

Since 1968, botanists have been on the lookout for skunk cabbage, now 18 counties in North Carolina have been reported as having at least one population.

Using herbarium records — now conveniently cataloged from herbaria across North America on sernecportal.org (a resource which Radford, Ahles and Bell did not have in 1968!) — I have targeted two populations of skunk cabbage which I would like to re-find. In August 1937, Donovan & Helen Correll documented skunk cabbage in “wet swampy woods near Mt. Carmel” in Forsyth County. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) does not have a specimen from Forsyth County. Instead, the Corrells deposited their specimens in the Duke University Herbarium (DUKE) and the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University (GH). Unfortunately, I have been unable to find a place named “Mount Carmel” and there are at least half a dozen churches by that name in Forsyth County. Clearly re-finding the Corrells’ skunk cabbage will require lots of research using maps from that era, lots of tramping around wet woods, and a good dose of luck.

Person County had (and hopefully still has!) two populations of skunk cabbage. Dr. Radford deposited a single specimen in NCU which he’d collected in June 1960 from “Bog, near Marlowe Creek, 1.2 miles west of Woodsdale.” Marlowe Creek is quite long, but the portion west of Woodsdale and north to its confluence with Storys Creek looks like a good place to start the search. Shaub Dunkley (likely a student at UNC-Chapel Hill) deposited in NCU a very nice specimen with both leaves and remnants of the spathe collected in April 1977 from “Low swampy area, southernmost inlet to pond of Linsey & Kenneth Wagstaff, off NC 1309, 0.5 mi to jct NC 1300, ca 1.6 mi SW of US 57; Olive Hill Community.” With any luck, the Wagstaff family is still in residence, has their name on their mailbox on SR 1309, and is willing to let me search their land for skunk cabbage!

As skunk cabbage is much easier to find once it has finished flowering and its leaves have fully expanded to being knee-high, I will wait until May and June to continue my quest for Symplocarpus foetidus in the woodlands and wetlands of the North Carolina Piedmont. If you spy any skunk cabbage let me know — together we can collect a specimen for the Herbarium!

SOURCES:

- Nicholson, Barbara J. and Sylvia L. Halkin. 2007. Temperature relationships in Eastern Skunk Cabbage. Bioscene 33(2): 6-14.

- (2021) Pollination ecology of Symplocarpus foetidus (Araceae) in a seasonally flooded bog in Québec, Canada, Botany Letters, 168:3, 373-383.

- Wikipedia contributors, “Chironomidae,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chironomidae&oldid=1043974809 (accessed February 27, 2022).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Sphaeroceridae,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sphaeroceridae&oldid=1059494002 (accessed February 27, 2022).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Mycetophilidae,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mycetophilidae&oldid=1066769817 (accessed February 27, 2022).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Phoridae,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Phoridae&oldid=1044125802 (accessed February 27, 2022).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Chloropidae,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chloropidae&oldid=1074160318 (accessed February 27, 2022).

- Wikipedia contributors, “Anthomyiidae,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Anthomyiidae&oldid=1041316265 (accessed February 27, 2022).

- Cassebaum, Anne Melyn. 2011. Down Along the Haw: The History of a North Carolina River. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Inc.

- “Lake Townsend” City of Greensboro. https://www.greensboro-nc.gov/departments/parks-recreation/the-lakes/lake-townsend accessed 27 February 2022.