by Zachary Bradford

Chesapeake Bay Region Steward, Virginia Natural Heritage Program

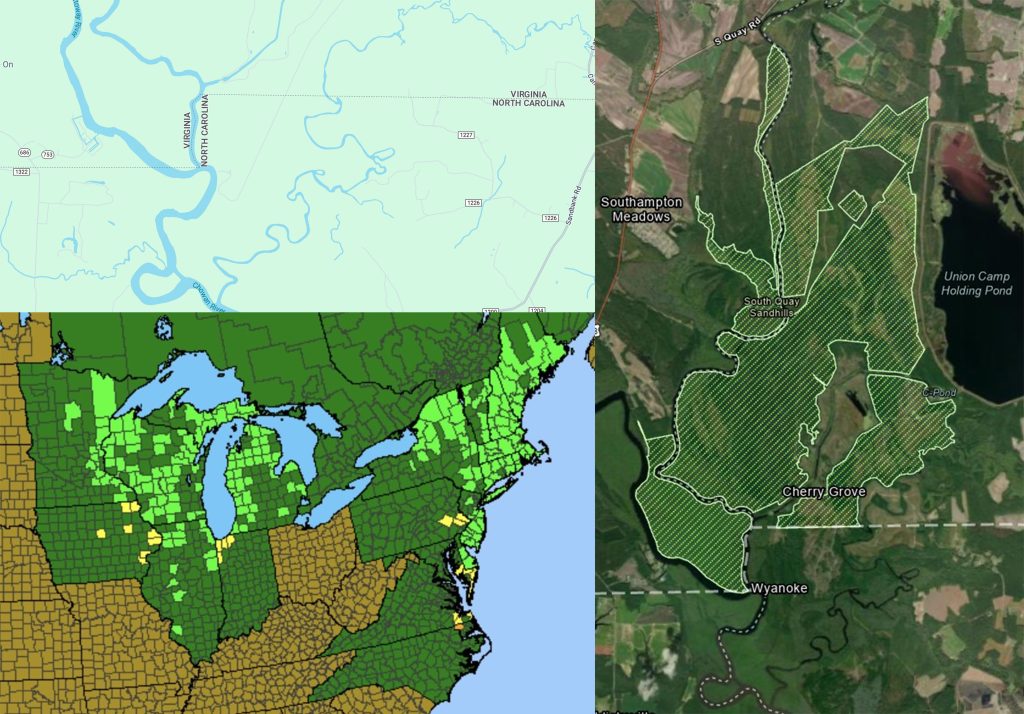

It’s an October tradition for the Virginia Natural Heritage Program’s southeastern stewardship staff to harvest longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) cones from the world’s northernmost naturally occurring, mature stand at South Quay Sandhills Natural Area Preserve (SQSNAP). We spend about a week in a bucket truck picking cones to provide northern genotype seed for longleaf pine restoration efforts in southeast Virginia. SQSNAP sits on the Virginia – North Carolina line and occupies the northern reaches of the Chowan Sand Banks, an ancient deposit of xeric white sand that stretches south into Gates County, North Carolina, and largely parallels the east side of the Chowan River. These sands are home to a number of sandhill and southeastern species that “jump the gap” from North Carolina’s fall-line sandhills.

In October, the sandy roadsides adjacent to the longleaf pine stand at SQSNAP are dotted with patches of wispy northern wireweed (Polygonella articulata). I never paid it much attention; it’s abundant enough in Virginia, primarily in coastal maritime woodlands, that Virginia’s Natural Heritage Program doesn’t track it as a rare species. I always figured it was like common October-flower (Polygonella polygama): a southeastern species at or near its northern range limit in Virginia. Upon realizing that I didn’t know anything about northern wireweed, I referenced its range map on the Biota of North America Project (BONAP) website and was met with two surprises. First, I was completely wrong about the range. Unlike all other Polygonella, northern wireweed is primarily a species of New England and the upper Great Lakes region and only reaches south along to Atlantic seaboard as far as Gates County, North Carolina. It certainly seemed in opposition to the prevailing southeastern botanical flavor of the site. The second surprise was that Gates County was shaded orange in BONAP, meaning the species is considered historic or presumed extirpated in North Carolina. This was doubly perplexing because there is no shortage of northern wireweed just one kilometer north of the state line in the longleaf pine stand at SQSNAP.

Northern wireweed had been seen once in North Carolina: on October 8, 1959, on a “sandy roadside, Wyanoke, ssw. of Va 189 drawbridge over the Backwater River.”1 The collection was made by future Western Carolina University professor James Heathman Horton, and he was accompanied by NCU Herbarium curator Harry E. Ahles. Wyanoke, the site of a long defunct ferry across the Chowan River, is situated on a two-and-a-half kilometer-long triangle of land cut off from the rest of North Carolina by the Chowan and Blackwater Rivers to the west and by Somerton Creek to the east. This area, now part of Chowan Swamp Game Land, is only accessible over land via Virginia’s SQSNAP to the north. This isolation and associated access logistics undoubtedly decreased the number of botanically-inclined people that have visited the area over the years.

I relayed what I found out to my colleague Darren Loomis who has been managing SQSNAP for well over a decade. He knew just the place to look: shortly before reaching North Carolina the sand road to Wyanoke forks, with a smaller unmaintained road heading in a more easterly direction towards Somerton Creek. We took this side road to the state line. Both adjacent landowning agencies practice prescribed fire on their respective properties, so the North Carolina side of the state line also serves as a maintained fire break to help keep prescribed fires in the correct states. Just as Darren predicted, before even parking the truck we could see a haze of pink northern wireweed on the state line and on the sandy roadsides beyond. While our find on October 17, 2023, is the first time northern wireweed has been positively identified in North Carolina since the Horton and Ahles collections in 1959, I have to give credit where it is due. Both North Carolina Wildlife Commission and North Carolina Natural Heritage Program staff have previously collected what was probably northern wireweed in the same vicinity but specimens were too immature for positive identification.

Coincidentally, northern wireweed isn’t the only northern species at its southern range limit in the “Wyanoke triangle” of Gates County, North Carolina. In 2005, after seeing the abundance of sheep laurel (Kalmia angustifolia) at SQSNAP, Virginia Natural Heritage Program Botanist Johnny Townsend looked across the state line in the same area and vouchered it as new to North Carolina.2

Addendum by Carol Ann McCormick, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium Curatrix:

Botanists are always on the lookout for other plants that may jump the gap between states. Ruth’s golden-aster (Pityopsis ruthii in the Aster Family) has been documented from southeastern Tennessee, but never found in neighboring North Carolina. Dwarf greenbriar (Smilax pumila in the Catbrier Family), sandhill rosemary (Ceratiola ericoides in the Blueberry Family), and mullein foxglove (Dasistoma macrophyllum in the Broomrape Family) have all been documented from South Carolina, but never from North Carolina.

What about plants that are found in North Carolina but not in South Carolina? “Cooley’s meadowrue (Thalictrum cooleyi in the Buttercup Family) is rude in that way — it is found in North Carolina, skips South Carolina and maybe Georgia too, but then is found in Florida,” says Eric Ungberg, botanist with South Carolina Heritage Trust. “Short-awned tickseed and Carolina maritime goldenrod (Coreopsis aristulata and Solidago villosicarpa in the Aster Family) are thus far confined to North Carolina and have not deigned to grace South Carolina with their presence. Golden crest (Lophiola aurea in the Bog-asphodel Family) is found from Nova Scotia to Florida, and grows in North Carolina very close to the South Carolina border, but has yet to be documented in South Carolina,” continues Ungberg.

There are success stories, as Zach Bradford’s story above details for northern wireweed and sheep laurel. In September 10, 2003, Harry LeGrand of the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program found coastal plain nailwort (Paronychia herniarioides in the Pink Family) in Scotland County, North Carolina, a mere 208 years, 11 months, and 15 days since it had last been documented in The Old North State by Andre Michaux (1746-1802).3 Stiff clubmoss (Spinulum annotinum in the Clubmoss Family) was known to grow in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia, and botanists were confident that it could jump the gap into North Carolina. In 2022, community scientists J. Thomas Jones, Jr. and Mary G. Douglass found it growing in Haywood County, NC.4 Botanists hope to document a natural population in Tennessee.

Keep those field guides handy, pay close attention to state lines, and you too may be able to jump the gap and find a State Record, or a plant that has not been documented for a century or so. If you think you’ve struck gold, take several photos, note your exact location, and contact your state’s Natural Heritage Program.

- Horton & Ahles collected several specimens of Polygonella articulata: NCU accessions 161550, 161551, 161552, and 161553. Western Carolina University (WCUH accession 10807) also curates a specimen collected by Horton & Ahles on 8 October 1959. Wilson # 1546 from the Croatan National Forest, Craven County, NC curated by UNCC (accessions 20591) is likely Polygonella polygama, Common October-flower.

- Townsend #3487, Kalmia angustifolia, NC: Gates County; NCU accession 580035. Townsend #3486, Kalmia angustifolia, NC: Gates County; NCU accession 580036.

- Weakley, Alan. 2004. In the Footsteps of Andre Michaux? North Carolina Botanical Garden Newsletter, January-February, 2004: 9.

- McCormick, Carol Ann. 2023. Citizen Science at the Herbarium. The Conservation Gardener, Spring/Summer 2023: 10-12.