By Gary Perlmutter, Herbarium Associate & Carol Ann McCormick, Herbarium Curatrix

Identifying lichens can be a painstaking and difficult practice and often employs several different techniques. First is morphological examination, i.e., looking at the lichen’s color, size, and shape. A few species are readily identifiable in the field. Common Greenshield Lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata) has large, yellow-green leaf-like lobes, grows attached to tree bark, and is usually easy to identify on sight. Another lichen that grows upon trees, particularly trees in sunny areas, is Candleflame Lichen (Candelaria concolor). It is a bit smaller than Greenshield Lichen, but still distinct as it sports bright yellow frilly lobes. However, many lichen species need more detailed study in the lab to discern their true identity. A compound microscope is needed to examine the internal anatomy of the body (thallus) of a lichen or to examine the reproductive structures (ascomata) of the lichen. Some species need chemical testing to see what metabolites they produce, since many of these chemicals are specific to certain lichens and thus aid in identification. (It is these complex metabolites that make lichens useful as medicines, as natural dyes, and even as components in perfume. For the lichens, these metabolites may deter herbivores and may help break down the rocks or soil upon which they grow.1 ) Finally, some species can only be determined using genetic analysis, i.e. DNA sequencing.

Heart Lichens in the genus Cora are leaf-like mushroom lichens that live in the tropics of the Americas. A morphologically distinct group with smooth, round and ringed lobes, they were once known as a single species: Cora pavonia. But recent genetic analyses have revealed Cora to be a hyper-diverse group of species. Lichenologists predict that there are likely 450 species in the group, of which only a fraction have been fully investigated and described.2, 3

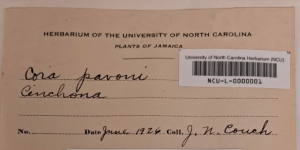

The lichen collection in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) includes two specimens of Cora. These were collected by John Nathaniel Couch (1896-1986) in Jamaica in 1926, nearly 100 years ago. One was determined as C. pavonia by Robert Lucking, an expert in the genus, while the other specimen was considered a possible mixture of different species. The best way to identify it was by sequencing its DNA.

Fortunately, DNA from historical specimens can be sequenced, as demonstrated by Dr. Paul Gabrielson’s work on red algae collected by naturalist Tadeus Haenke aboard the Descubierta (“Discovery”) on Captain Alessandro Malaspina’s round-the-world voyage 232 years ago.4 Historical Cora specimens have also been successfully sequenced by Dr. Manuela Dal Forno, a lichenologist at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas.5 Fortunately Dr. Dal Forno agreed to sequence the DNA of the Cora which Dr. Couch collected in 1926. Shanna Oberreiter, the Herbarium’s Loans Manager, packaged up the specimen and mailed it to Dr. Dal Forno’s lab in Fort Worth, Texas.

In July, 2023, Dr. Dal Forno returned Couch’s specimen to Chapel Hill, along with with notes, a GenBank accession number and determination of it as C. pavonia, verifying

J.N. Couch’s original identification. Dal Forno submitted the specimen’s DNA sequence into the GenBank repository for access by the scientific community for further study.6

In 2010 the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Herbarium (NCU) joined the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria.7 Funded by the National Science Foundation, lichenportal.org is a centralized database where herbaria across the globe can catalog lichen specimens. As of August, 2023, a total of 175 herbaria participate in this consortium, making it the go-to source of information on lichen specimens curated in herbaria.

In 2011 Herbarium Associate Gary Perlmutter started cataloging specimens in lichenportal.org and his first task was to affix a barcode to each specimen. Just like a library book, this barcode serves not only as a unique identifier for the specimen, it can also be read by a scanner so that when we lend the specimen it can easily be “bleeped” as it is checked out and again “bleeped” when it returns to show that it is back home, ready to be re-filed, and available to other borrowers/researchers.

In a happy coincidence, John Nathaniel Couch’s Cora specimen was the very first lichen at NCU to be cataloged — it was given the very first barcode: NCU-L-0000001. A dozen years later it was the very first lichen in our collection to have its DNA sequenced!

Cora specimen’s collector: John Nathaniel Couch

History buffs may be interested to learn that Dr. John Nathaniel Couch (1896-1986) was a student of the founder of the Botany Department at Carolina, Dr. William Chambers Coker (1872-1953). Couch joined the Carolina faculty in 1922, and succeeded his mentor as Chair of the Botany Department. Over his long career as teacher and researcher, Couch guided the studies of 27 master’s and 15 doctoral students at Carolina. He retired in 1968.8 His daughter, Sally Louise Couch Vilas (1931 -2023) had a long association with the North Carolina Botanical Garden. She served on the Botanical Garden Foundation Board, including two terms as president of that body.9

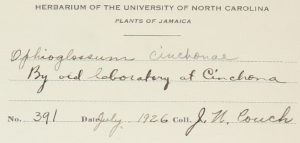

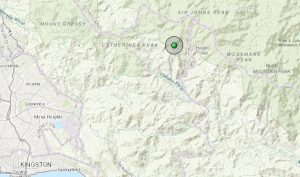

Dr. Couch spent the entire summer of 1926 in Jamaica — we know this as we can track his movements by examining the labels of the herbarium specimens he collected! Over the course of the summer, he collected 23 lichens, 57 macrofungi, and at least 393 vascular plants in places such as “Blue Mountain Peak”, “Abbey Green”, “Portland Gap”, “Mossman’s Peak” ,”Hardware Gap [sic; Hardwar Gap]”, and “Cinchona”.7, 10,11

Cinchona: plant or place in Jamaica?

The label for the Cora lichen that was sequenced is quite brief (see image at right), and at first we took “Cinchona” for the substrate upon which the lichen was growing. Cinchona (“Fever Tree” or “Jesuit’s Bark”) is a genus of about two dozen species of trees and shrubs native to tropical forests in South America. However, as several species are the source of quinine, the plants have been cultivated across the globe.12 “In the early 1870’s several species of cinchona seedlings were planted on seven hectares of a ten hectare property. Thus the Garden was called Cinchona Garden. The bark of the cinchona plant produces an extract called quinine, which is of great medicinal value as it is utilized in the treatment of diseases like malaria. By 1874, Cinchona became the centre for experimental botanical work within the island. Along with cinchona, other plant species were introduced by Mr. Nock from Kew Gardens to give Cinchona a wide variety of plant species… [In 2020] the garden buildings are in a dilapidated condition. However, Tourism Enhancement Funds (TEF) of approximately J$13 million was secured to facilitate the restoration of all the buildings, establishment of a Plant Nursery, development of a camp site and rehabilitation of hiking trails to the garden.”13

We know from other specimens collected that summer that Dr. Couch spent time at Cinchona Botanical Garden (see label at left). At an elevation of 4800-5200 feet in the mountains northeast of Kingston, it does seem an ideal place for a biological station. Herbarium staff now consider the “Cinchona” on the Cora label to be the place where it was collected, not a plant that the lichen grew upon.

Dr. Couch’s Jamaican summer was a productive one. In addition to collecting hundreds of specimens for the Herbarium, he discovered and named two new species of fungi from the island: Septobasidium purpureum Couch and Septobasidium alveolatum Couch.

If you are planning a trip to Jamaica consider including a pilgrimage to Cinchona Botanical Garden to walk in the botanical footsteps of John Nathaniel Couch! In June, 2022 Dr. Kim Walker, whose research at Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew focuses on medicinal plants, visited Jamaica and reports, “Cinchona Garden is very well maintained, though the original buildings are long since abandoned. The roads to approach it are in great disrepair — you need a very sturdy 4×4 and a confident driver. It’s about a 3 hour drive from Kingston (despite maps saying 1.2 hours) because you have to drive so slowly. You have to walk the last third of a mile to get to the Garden. Arriving is a strange feeling after such a rough journey through the hot tropical forests, to arrive at a cool, misty English style garden at the end!”14

For more information on the history of gardens and plantations in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, follow the work of Dr. Thera Edwards in the Department of Geography & Geology at The University of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica. She is an authority on the history of the gardens at Cinchona.15,16

If you’d like to learn more about Dr. Manuela Dal Forno’s work, watch “Exploring the Amazing World of Lichens with Manuela Dal Forno,” produced by the Smithsonian Institution. The video is about 30 minutes in length.

REFERENCES

1. De Santis, Salvatore. 1999. An Introduction to Lichens. New York Botanical Garden. https://www.nybg.org/bsci/lichens/ accessed on 26 August 2023.

2. Lücking, R. et al. (2017) Turbo-taxonomy to assemble a megadiverse lichen genus: seventy new species of Cora (Basidiomycota: Agaricales: Hygrophoraceae), honouring David Leslie Hawksworth’s seventieth birthday. Fungal Diversity 84(1): 139-207.

3. Moncada, B., R.E. Pérez-Pérez & R. Lücking (2019) The lichenized genus Cora (Basidiomycota: Hygrophoraceae) in Mexico: High species richness, multiple colonization events, and high endemism. Plant and Fungal Systematics 64(2): 393–411.

4. McCormick, Carol Ann. 2010 November. Voyages of Discovery: novel information from old herbarium specimens. North Carolina Botanical Garden Newsletter, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

5. Dal Forno, et al. (2022) DNA barcoding of fresh and historical collections of lichen-forming Basidiomycetes in the genera Cora and Corella (Agaricales: Hygrophoraceae): A success story? Diversity 14: 284.

6. Cora pavonia isolate NCU-01 small subunit ribosomal RNA gene and internal transcribed spacer 1, partial sequence. GenBank: OR096289.1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OR096289 accessed on 27 August 2023.

7. Consortium of Lichen Herbaria (2023) http//:lichenportal.org/portal/index.php. Accessed on August 27.

8. Gilmour, Ron, William Burk, Jimmy R. Massey, Mary McKee Felton, James Murphy and Carol Ann McCormick. 2021. John Nathaniel Couch. https://ncbg.unc.edu/2021/04/26/john-nathaniel-couch/ accessed on 27 August 2023.

9. Tribute Archive, Walkers Funeral Home. 2023. Sally C Vilas. https://www.tributearchive.com/obituaries/27058424/sally-c-vilas accessed on 27 August 2023.

10. MyCoPortal . 2023. http://www.mycoportal.org/portal/index.php. Accessed on August 27.

11. SERNEC Data Portal. 2023. http//:sernecportal.org/index.php. Accessed on August 27.

12. Wikipedia contributors. “Cinchona.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 Aug. 2023. Web. 27 Aug. 2023

13. “Cinchona Botanical Garden” 2020. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Mining. Jamaica. https://www.moa.gov.jm/content/cinchona-botanical-gardens accessed on 27 Aug 2023.

14. personal communication, Walker to McCormick, 2023.

15. Edwards, Thera. 2014. Toward an historiography of the Hill Gardens at Cinchona, Jamaica. Caribbean Geography 19: 69-88.

16. Edwards, Thera Hyacinthe. 2013. Plantations, Profits and Protection: An Environmental History of the Blue Mountains, Jamaica, 1800-2009. University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica.